An Iron Pavilion, an Organ and a Colonial Garden

IT WAS IN APRIL 2011 when I last visited the Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale in the Bois de Vincennes at Nogent-sur-Marne on the eastern edge of Paris. Then, I went there several times to record sounds for the 2011 Paris Obscura Day event organised by Adam, curator of Invisible Paris.

Recently, I decided it was time to return to Nogent-sur-Marne and explore a little more.

Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale

I am fascinated by industrial archaeology and particularly by the mid-nineteenth century iron and glass structures to be found in Paris – structures like la Grande Halle de la Villette or Henri Labrouste’s sumptuous reading room at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève.

Sadly, I was never able to see the eight Victor Baltard iron and glass pavilions at Les Halles, the traditional central market in Paris founded in 1183.

Les Halles, the former central market in Paris. Photograph: Sophie Boegly/Musée d’Orsay

Unable to compete in the new market economy and in need of massive repairs, the central market was relocated to Rungis, south of Paris, in 1971 and all but two of Baltard’s iron and glass pavilions were destroyed. The two that survived were dismantled and then re-erected, one in Yokohama, Japan and the other in Nogent-sur-Marne.

When I went back to Nogent-sur-Marne recently I sought out this surviving Baltard pavilion.

The Pavillon Baltard, Nogent-sur-Marne

This pavilion was used originally for selling eggs and poultry at the Les Halles market. Today it’s surround by iron gates – the original gates from Les Halles – and it’s used for a variety of events including concerts, exhibitions and corporate functions.

Unfortunately, I was not able to gain entry to the pavilion, which was a shame because as well seeing the pavilion itself I particularly wanted to see something housed inside.

As well as acquiring the Baltard pavilion, Nogent-sur-Marne also managed to acquire the four manual, sixteen rank, Christie cinema organ once housed in the massive 5,500 seat Gaumont Palace cinema in Paris. Built in 1931 by the English organ builders, Hill Norman and Beard, the organ now resides in the Baltard pavilion.

The art-deco Gaumont Palace cinema in Paris

This famous theatre organ will always be linked with the organist, Tommy Desserre, who played the instrument until the Gaumont Palace closed in 1972.

The Christie organ console in the Pavilion Baltard

Although I wasn’t able to go in and see the organ, I have found this 1988 recording of John Mann playing an Hommage to Edith Piaf on the organ in the Baltard pavilion so you can hear what it sounds like.

Having seen the Baltard pavilion, if only from the outside, I took myself off to a nearby bistro for lunch where I found this lady posing for me.

After lunch I decided to make a return visit to the Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale at the eastern edge of the Bois de Vincennes. The last time I was here I spent four days recording sounds for Adam’s Paris Obscura Day event so I was anxious to see what sounds I might capture on this summer’s day.

I settled myself down beside the Indochinese temple and began to record the wildlife, the rustle of the bamboo trees and the ever-present man-made sounds around me.

Summer sounds in the Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale:

The Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale was created in 1899 as a ‘jardin d’essai colonial’, a research garden, with the aim of coordinating agricultural experiments that would lead to the introduction or reintroduction of exotic plants like coffee, bananas, rubber trees, cocoa and vanilla across the French colonies.

During the summer of 1907 the garden became the site of a Colonial exhibition organised by the French Colonisation Society.

The exhibition was designed not only to show off exotic plants, animals, and other products of the French empire but also to show off people from the colonies who lived in five different villages on the site recreating their ‘typical’ environments. There were villages for people representing the Congo, Indochina, Madagascar, Sudan, and New Caledonia as well as a camp for the Tuaregs from the Sahara.

This ‘human zoo’ proved to be very popular attracting around one and a half million visitors.

The Tuareg camp at the 1907 exhibition

At the end of the summer of 1907 the exhibition closed, the residents returned home and the exhibition site was left abandoned. During World War II, the site was used as a hospital for colonial troops and in the post-war years part of it housed the École d’agronomie tropicale and the Centre technique forestier tropical. The remnants of the Colonial villages though were left to decay.

In 2003, the city of Paris acquired the site and began a development programme and the garden was opened to the public in 2006.

Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale – The Colonial Bridge

Even though I didn’t get to see the Christie cinema organ, I enjoyed my day in Nogent-sur-Marne. Seeing the Pavillon Baltard has been on my ‘to do’ list for a long time and sitting in the Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale listening to its sounds was a delightful way to spend a summer afternoon.

Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale – The Indochina War Memorial

The Galerie Vivienne and its Sounds

OF ALL THE PARISIAN passages couverts that sprang up mainly in the first half of the nineteenth century, the Galerie Vivienne was perhaps the most fashionable.

The passages couverts, or covered passages, were an early form of shopping arcade concentrated either in the fashionable area around the Palais Royal, the Boulevard des Italiens and the Boulevard Montmartre, or around the less fashionable rue Saint-Denis.

Of the one hundred and fifty original passages couverts, only twenty now remain and I’ve been to all of them to record and archive their contemporary soundscapes for my Paris Soundscapes Archive.

The Galerie Vivienne was built in 1823 by the Président de la chamber des Notaires, maître Marchoux. Marchoux lived at N°6 rue Vivienne and he built the Galerie Vivienne around his house and three adjoining properties he acquired, including the former stables of the duc d’Orléans, and a terraced house and garden overlooking the rue des Petits-Champs.

The French architect, and winner of the prix de Rome in 1778, François-Jean Delannoy was commissioned to design and build the passage. His design successfully turned an irregular ‘L’ shaped, slightly inclined passage into a remarkably attractive shopping arcade while integrating the existing buildings.

Galerie Vivienne in the 1820s

The Galerie Vivienne was opened for business in 1826. It boasted seventy boutiques including a tailor, a boot-maker, a wine merchant, a restaurant, a haberdashery, a confectioner, an engravings dealer, a hosier and a glassblower. The gallery also hosted the Cosorama, where one could view scenes of distant lands and exotic subjects through optical devices that magnified the pictures and the Unanorama, where you could observe the stars.

The Empire style decoration inside the galerie combines arches, pilasters and cornices. The high glass ceilings are embellished with friezes representing the symbols of success (crowns of laurels, sheaves of corn and palms), of wealth (horns of plenty) and commerce (the caduceus of Mercury).

The Italian mosaic artist, Giandomenico Facchina, created the mosaic floor.

Sounds inside the Galerie Vivienne:

These are the contemporary sounds inside the Galerie Vivienne, recorded a few days ago. But we do have a record of the impression the nineteenth century sounds of the galerie made on one person: the composer, Hector Berlioz.

In 1830, a few days after the July Revolution, Berlioz went out into the streets of Paris and was mixed up with a crowd filling the Galerie Vivienne and the neighbouring Galerie Colbert. He writes in his Memoirs:

“It must be imagined that the gallery which terminated at the Rue Vivienne was full, that the one into the Rue Neuve des Petits-Champs was full, that the middle rotunda was full, that these four or five thousand voices were piled up in a sound-room closed to the right and left (…) at the top by stained-glass windows, at the bottom by resounding slabs (…), and one may imagine the effect of this fiery refrain (…) I fell to the ground, and our little company, terrified at the explosion, was struck with absolute silence, like the birds after a thunderclap.”

With the coming of the retail revolution in the mid-nineteenth century, the new department stores springing up across the city signaled the demise of all of the Parisian passage couverts.

When Hermance Marchoux, daughter of maître Marchoux, died in 1870 the Galerie Vivienne was bequeathed to the Institut de France, but by 1897 the gallery was deserted and in 1903 it faced the prospect of demolition.

It did manage to survive though although it wasn’t until the 1970s and the revival of interest in the architectural heritage of the passages couverts, that it gradually returned to life.

Kenzo held a fashion show in the galerie in 1970 and then, a little later, more fashion shops began to appear. It was the arrival of Jean-Paul Gaultier in 1986, which established the Galerie Vivienne once again as a place of Parisian high fashion. The lustre of the Galerie Vivienne had returned.

Two of the boutiques in today’s Galerie Vivienne have a long pedigree.

The wine merchant, arguably one of the best in Paris, Lucien Legrand Filles & Fils is one of the longest established boutiques in the galerie, still occupying its original position.

The oldest surviving boutique can be found at N° 45 Galerie Vivienne: the Librairie Jousseaume. Established in 1826, some say this is the oldest surviving bookshop in Paris.

The bookshop was bought in 1900 by M. Petit-Siroux who then bought the boutique opposite, at N° 46.

Located between the Palais Royal, the Paris Bourse and the Grands Boulevards, the Galerie Vivienne lies at the heart of fashionable Paris. Despite coming close to destruction at the turn of the nineteenth century, the galerie now boasts prestigious labels and quality artisans that link both past and present. The sumptuous architecture, delicate mosaics and grand statues have been wonderfully preserved, and the shops and restaurants are seriously chic and expensive!

From Epinay to Saint-Denis by Tram

PARIS TRAMWAYS DATE BACK to the mid-nineteenth century with the first city tram route opening in 1855. At its peak in the 1920s, the tramway network incorporated some 122 lines and upwards of 1,000 km of track. By the 1930s though, the internal combustion engine reigned supreme and the number of motor cars and motor buses on the roads signalled the end of the tramways. The last of the tram lines in Paris, Porte de Saint-Cloud to Porte de Vincennes, closed in 1937, and the last line in the entire Paris agglomeration, running between Le Raincy and Montfermeil, ended service in 1938.

Carte postale ancienne éditée par Cormault, N°136 Paris

Paris and the surrounding region had to wait for almost sixty years before a new tramway network began to appear with a new generation of trams. First came Line T1, opened in 1992 followed by Line T2 in 1997, Lines T3 and T4 in 2006, Lines T5 and T7 in 2013 and Lines T6 and T8 in 2014. Some of these lines have already been extended and further extensions are planned. And two further new lines are planned: Line T9 is scheduled to open in 2020 and Line T10 in 2021.

Of the nine tramways currently operating in the Île-de-France region (Line T3a and T3b count as two separate lines) most operate within the suburbs around Paris, with only two lines, T3a and T3b, running entirely within the city limits, although line T2 does so for part of its route.

One of the suburban tramways is Line T8, the latest tramway to be opened, and I went to take a ride on it.

Image courtesy of RATP

After a trial running of four weeks without passengers, Line T8 opened in December 2014. The tramway runs 8·5 km north from Saint-Denis – Porte de Paris to Delaunay-Belleville, where it splits into two branches, terminating at Villetaneuse-Université and Epinay-Orgemont. There are a total of 17 stops and, in another example of RATP’s joined-up thinking, interchange is provided with metro Line 13, tram line T1 and RER Line C.

I caught a tram at Saint-Denis and travelled to Epinay-Orgemont in Epinay-sur-Seine.

The journey took 22 minutes and included 13 stops, the other 4 stops being on the branch line to Villetaneuse.

Villetaneuse is planned to be a future station on the new Tangental North line, a €1.5 billion suburban tram-train line that will interchange with existing SNCF Transilien trains, trams, metro, and Réseau Express Régional (RER) lines A, B, C, D and E. This line is scheduled for completion in 2023.

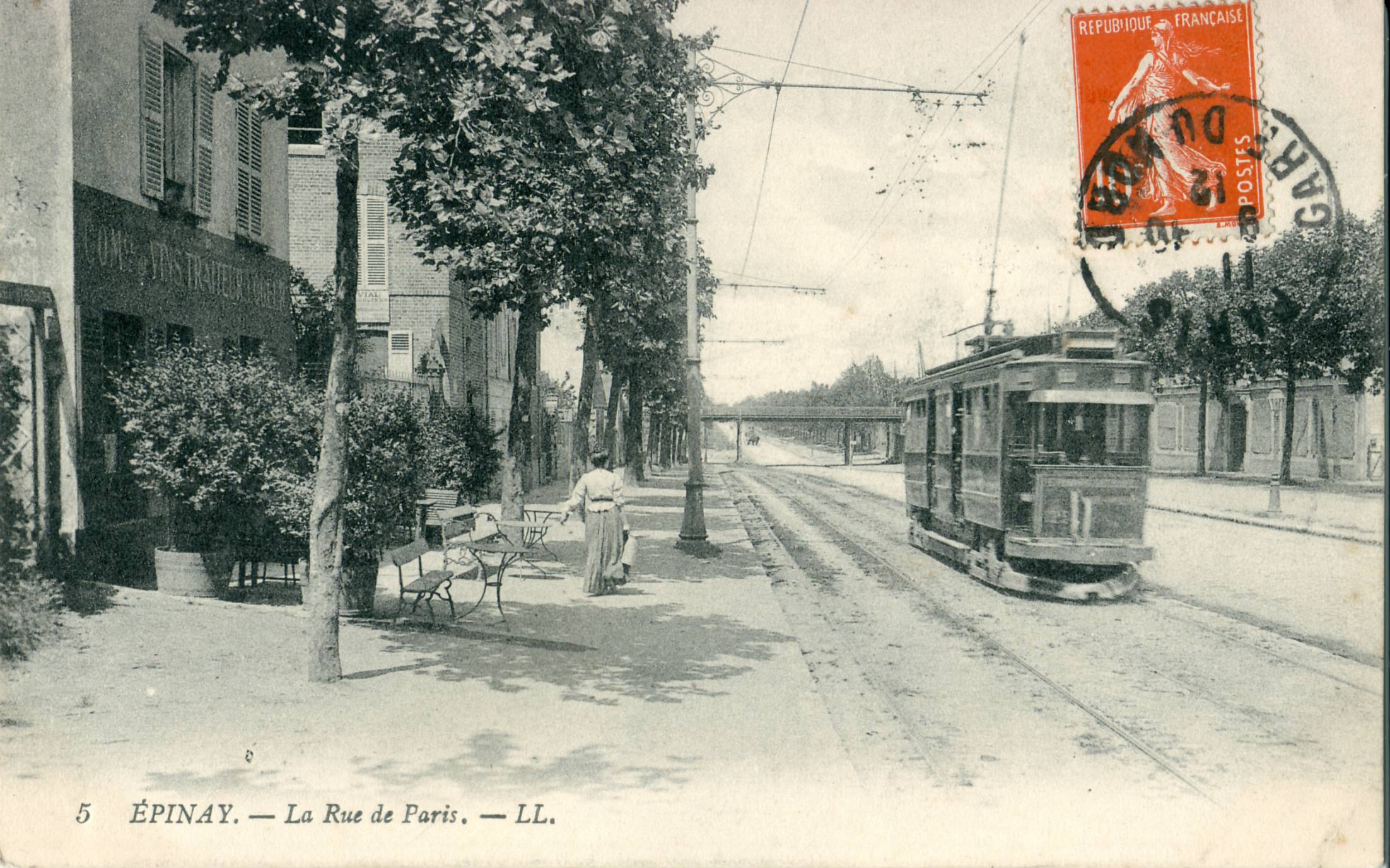

Epinay-sur-Seine is no stranger to trams. The tramway Enghien (Cygne d’Enghien) – Trinité (Église de la Trinité à Paris) was opened by the Compagnie des Tramways électriques du Nord-Parisiens on 26th September 1900. The line survived until March 1935 when it was replaced by a bus route.

Le Tramway Enghien-Trinité sur la route nationale à Épinay, avant 1912

I didn’t have to wait long for a tram for my return journey from Epinay to Saint-Denis. The trams run every six minutes, although along the stretch from the Delaunay-Belleville stop, where the two branch lines meet, to Saint-Denis they run every three minutes.

Tram Line 8 – Epinay-Orgemont to Saint-Denis – Porte de Paris:

Tram Line 8 operates with a fleet of 20 low-floor Alstom Citadis trams assembled at Alstom’s La Rochelle factory. Each tram is 32 metres long and 2.4 metres wide, made up of five sections with capacity for 200 passengers. The trams include air-conditioning, CCTV, a passenger counting system and audiovisual passenger information. Some 55,000 passengers use Tram Line 8 every day, which amounts to 16 million passengers per year.

Constructing Tram Line 8 was a formidable task. The project, implemented by GCF, Generale Costruzioni Ferroviarie, in a consortium set-up with Esaf and Laforet, had to contend with a route running through a densely populated residential area characterised by a high volume of traffic. During construction, efforts were made to reduce pollution involving dust, gas and noise, as well as achieving maximum vibration reduction. Steps were also taken in advance over the entire length of the line to ensure the physical protection of trees by masking them to safeguard against the possible effects of shock caused by mechanical equipment.

Today, the tramway network around Paris amounts to some 105km of track with more still to come. The tramway network may be far short of its peak in the 1920s but riding today’s trams is a convenient and comfortable way to travel and I thoroughly recommend it.

Tram Line 8 Terminus at Saint-Denis – Porte de Paris

The City as a Perpetual Concert

SOME NINETEENTH CENTURY OBSERVERS of Paris were quite forthright in their impressions of the sonic tapestry of the city.

For example, the American writer John Sanderson arrived in Paris for the first time in July 1835 and he wasn’t over impressed with what he found …

“All things of this earth seek, at one time or another, repose – all but the noise of Paris. The waves of the sea are sometimes still, but the chaos of these streets is perpetual from generation to generation; it is the noise that never dies.”

John Sanderson, Sketches of Paris: In Familiar Letters to His Friends (1838)

And in 1837, the journalist and flâneuse Delphine de Girandin wrote …

“In Paris today, the day is a perpetual concert, a series of uninterrupted serenades; Parisien ears have not one instant of rest.”

Delphine de Girandin: Lettres parisiennes du Vicomte de Launay: August 25, 1837

For John Sanderson the ‘noise that never dies’ included the sound of the notorious cries de Paris, the often piercing cries of the street traders hawking their wares, as well as the sound of traffic:

“… this rattling of cabs and other vehicles over the rough stones, this rumbling of omnibuses.”

Delphine de Girandin’s ‘perpetual concert’ was aimed at the itinerant street musicians:

“Starting in the morning, the organs of Barbary divide up the neighbourhoods of the city; an implacable harmony spreads over the city. [ … ] Finally, in the evening, great serenades! Violins, galoubets, flutes, guitars, and Italian singers! It’s a concert to die for, and there is no refuge; all this takes place under your window, it’s a residential concert that you cannot possibly avoid.”

And so to Paris in the twenty-first century; has anything changed?

The kind of sounds that John Sanderson and Delphine de Girandin encountered still exist in modern day Paris although the emphasis has changed.

The cries de Paris are now largely confined to the traders in the street markets although one can still come across men (it’s almost always men) calling out ‘Le Monde’ as they meander from café to café selling the afternoon edition of the daily newspaper. The street musicians still ply their trade although not quite so prolifically as in the nineteenth century. And then there’s the traffic! The sound of traffic pervades almost every nook and cranny of the city today and it can be overpowering and it’s perpetual; it really is the noise that never dies.

I spend a lot of time listening to Paris, so the notion of the city as a perpetual concert chimes with me. For me, it’s not just the street music that forms the concert, but rather all the sounds of the city. I see each individual sound, musical or not, as a dot on a score which, when added together, form a complete sonic composition. Or, to use a different metaphor, one might consider individual sounds as the warp and the weft, which, when woven together, form a sonic tapestry depicting the city.

Perhaps I can illustrate the notion of the city as a perpetual concert by recounting my perambulation around a part of Paris last Saturday afternoon.

I began at the Jardin du Luxembourg where I came upon this gentleman playing one of Delphine de Girandin’s organs of Barbary.

Street organ at the Jardin du Luxembourg:

Outside the gates of the Jardin du Luxembourg this little street organ sounds quite charming but, in different circumstances, I take Delphine de Girandin’s point: “ … there is no refuge; all this takes place under your window, it’s a residential concert that you cannot possibly avoid.”

Listening to this street organ, it’s impossible not to notice the pervading background sound of the passing traffic.

So let’s consider the sound of traffic, or as John Sanderson put it: “… this rattling of cabs and other vehicles over the rough stones, this rumbling of omnibuses.”

From the Jardin du Luxembourg, I walked the short distance to the Église Saint-Sulpice and then to the Place Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

The Place Saint-Germain-des-Prés is home to the church of the former Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, founded in the 6th century, and the famous café Les Deux Magots, once the rendezvous of the literary and intellectual élite of the city.

But for our purposes, the important thing about the Place Saint-Germain-des-Prés is that it is paved with John Sanderson’s rough stones.

When people ask me what my favourite sound of Paris is I usually decline to answer. But if asked what sound most typifies Paris then my answer is unequivocal: “… this rattling of cabs and other vehicles over the rough stones, this rumbling of omnibuses.”

Traffic over the pavé in Place Saint-Germain-des-Prés:

The Place Saint-Germain-des-Prés revealed the sounds of passing cycles, cars, the occasional two-wheeler, a luggage trolley and, with a nod to John Sanderson, at least three omnibuses.

And these sounds deserve to be listened to attentively because, thanks to the pavé, the pervasive, noise polluting, cacophonous traffic noise that blights this city seems to have been transformed into a soporific, almost musical composition.

My guess is that most of the people in Place Saint-Germain-des-Prés on Saturday afternoon were probably unaware of these sounds other than providing them with a faint sonic background to their dash from the church to the café. Yet for someone wired up like me, these sounds not only form part of the perpetual concert but they also screech, Paris!

Having listened so far to modern day examples of Delphine de Girandin’s organs of Barbary and John Sanderson’s rattling of cabs and other vehicles over the rough stones, it’s possible to take the notion of the city as a perpetual concert a stage further.

A few steps away from the Place Saint-Germain-des-Prés is the Rue de l’Abbaye, a street named after the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. It’s a narrow street running some 170 metres from Rue Guillaume Apollinaire to Rue de l’Echaudé and, although Paris is a bustling, sound rich city, Rue de l’Abbaye is one of the few streets shrouded in relative quiet.

So can a quiet street like Rue de l’Abbaye contribute to our perpetual concert? To find out, I perched myself on the steps of N° 3 Rue de l’Abbaye, the Institut Catholique de Paris, known in English as the Catholic University of Paris, and began to record.

Sounds in rue de l’Abbaye:

In Rue de l’Abbaye we find the human and avian species intertwined; the footsteps, the voices and the rustle of clothing as people pass by interlaced with the gentle cooing of the pigeons enjoying a late lunch and the flapping of their wings as they flutter to and fro in search of a tastier morsel. The occasional traffic sounds are in proportion to the surrounding ambient sounds rather than dominating them.

It takes concentrated listening to get the most out of these sounds but the effort is worth it because what is revealed is yet another strand to the city as a perpetual concert.

To complete my afternoon’s listening I returned to the Place Saint-Germain-des-Prés and one of Delphine de Girandin’s great serenades! Not the violins, galoubets, flutes, guitars, and Italian singers she referred to but instead, the Dixieland jazz style of the early twentieth century.

Jazz in Place Saint-Germain-des-Prés:

This group of jazz musicians can be found most Saturdays at the southwest corner of Place Saint-Germain-des-Prés entertaining an enthusiastic audience comprising mostly tourists.

In conclusion, I look upon Paris as a city of perpetual concert in which all the sounds the city has to offer, ranging from the loud, brash and often unwelcome to the subtle and understated, are performers of equal value. John Sanderson refers to the noise that never dies and Delphine de Girandin to Parisien ears have not one instant of rest, both of which are true: the city is never without sound so the concert is perpetual. It’s just a question of learning to appreciate it.

Important Listening Note:

It’s a quirk of our times that when we listen to recorded sound we tend to crank up the volume too much. In order for you to appreciate the sounds featured in this post I have set the levels so that the sounds correctly relate to each other. In other words, the sounds will replay at the same level relative to each other as I heard them when they were recorded.

To get the best effect, set the level of your listening device to the sounds of the street organ remembering that less is always more! Then keep your listening device set to the same level for all the other sounds.

Enjoy!

Église Saint-Germain-des-Prés

In and Around Métro Lamarck-Caulaincourt

NAMED AFTER THE FRENCH comedian, humorist and member of the French Resistance, rue Pierre Dac is just 23 metres long making it one of the shortest streets in Paris. Originally forming the upper part of rue de la Fontaine-du-But linking rue Lamarck and rue Caulaincourt in the 18th arrondissement, the street’s name was changed in 1995 in honour of Pierre Dac.

The distinctive red sign in rue Pierre Dac points us towards the Métro station Lamarck-Caulaincourt and tells us that this station once formed part of the three Paris Métro lines owned by the Nord-Sud Company, or to give it its proper name, la Société du chemin de fer électrique souterrain Nord-Sud de Paris. In 1931, the Nord-Sud Company was taken over by its competitor, la Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris, which in turn was nationalised in 1948.

The Métro station Lamarck-Caulaincourt is perhaps best known for its distinctive entrance nestling between the two staircases that form most of rue Pierre Dac.

Lamarck-Caulaincourt station was opened on 31st October 1912 and today it forms part of the Paris Métro Line 12 linking the stations Front Populaire in the north to Issy-les-Moulineaux in the south. The station platforms were renovated in 2000 – 2001 and further work was carried out in 2006.

Lamarck-Caulaincourt platform before renovation

Lamarck-Caulaincourt platform today

Since Lamarck-Caulaincourt station was constructed under the butte Montmartre, the large hill that forms the village of Montmartre, it’s not surprising that the station platforms are some 25 metres below the station entrance. For those who arrive at the station by train and find the 25-metre climb out of the station a challenge, RATP have thoughtfully provided a lift to make life easier.

Sounds around Lamarck-Caulaincourt station platforms and an exit by lift:

I recorded the sounds inside the station to add to my extensive archive of sounds of the Paris Métro network but I also recorded sounds from the staircases in rue Pierre Dac outside the station, which I found to be equally fascinating.

I sat on one of the staircases and simply observed life passing by just as the photographer did in the 1925 photograph below.

L’entrée de la station de métro Lamarck-Caulaincourt entre les escaliers de la rue de la Fontaine-du-But, vers 1925. Photo collection Jean-Pierre Rigouard.

Sounds from the staircase in rue Pierre Dac:

Entrance to the Métro station Lamarck-Caulaincourt between the staircases in rue Pierre Dac (formerly la rue de la Fontaine-du-But), August 2017

Sitting on a staircase in the street observing the world passing by might not be everyone’s idea of a good day out, but at least I wasn’t the only one!

Observing through active listening is what I do and whether it’s the sounds of a Métro station platform or the sounds of a staircase in the street I’m always captivated by the stories sounds have to tell to the attentive listener.

Although we can see from the photograph what this place looked like in 1925, I can’t help wondering what it sounded like then and what stories those sounds would have told us.

Gare d’Austerlitz and its Changing Sounds

SOME TIME AGO I reported that the Gare du Nord, one of the six main line railway stations in Paris and the busiest railway station in Europe, is undergoing a transformation. But it’s not only the Gare du Nord that is being transformed. On the left bank of the Seine, in the southeastern part of the city, another Parisian main line station is having a major facelift.

Since 2012, work has been underway at Gare de Paris Austerlitz, usually called Gare d’Austerlitz, to construct four new platforms, refurbish the existing tracks and rebuild the station interior. The renovation work will be completed by 2020 thus doubling the capacity of the station to accommodate some of the current TGV Sud-Est and TGV Atlantique services which will be transferred from Gare de Lyon and Gare Montparnasse, both of which are at maximum capacity.

The redevelopment of Gare d’Austerlitz is not confined to the station itself. It will also include developing some 100,000 M² of land between the station and the neighbouring Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière to include housing, offices, public facilities and businesses.

Built in 1840 to serve first the Paris-Corbeil then the Paris-Orleans line, the station, known originally as Gare d’Orléans, underwent its first makeover between 1862 and 1867 to a design by the French by architect Pierre-Louis Renaud, much of which is what we see today.

The name, Gare d’Austerlitz was adopted to commemorate Napoléon’s victory at the Battle of Austerlitz in December 1805.

Métro Line 5 arrived at Gare d’Austerlitz in 1906, the station survived the great flood of 1910 and in 1926 it became the first Parisian railway station to stop handling steam trains when electrification arrived.

Although the smallest of the Parisian main line stations, until the late 1980s Gare d’Austerlitz was one of the busiest with services not only to Orléans but also to Bordeaux and Toulouse. However, with the introduction of the TGV Atlantique using Gare Montparnasse, Gare d’Austerlitz lost most of its long-distance southwestern services and the station became a shadow of its former self. About 30 million passengers a year currently use Gare d’Austerlitz, about half as many as use Gare Montparnasse and a third as many as use the Gare du Nord.

The 21st century makeover of Gare d’Austerlitz will see the station upgraded to handle TGV trains, some of its former southwestern services restored and its capacity doubled.

Capturing the sounds of Paris is what I do and capturing changing soundscapes of the city has a special fascination for me. Any renovation of public spaces not only changes the visual aspect of the place but also its soundscape and so I am anxious to follow how the soundscape of the Gare d’Austerlitz will change as the current development unfolds.

This is what the station sounds like today:

Gare d’Austerlitz and its sounds:

It will be interesting to compare these sounds with sounds recorded from the same place in 2020 when the work is completed.

Of course, we don’t have to wait until 2020 to find a changing soundscape around Gare d’Austerlitz. We only have to go up from the main station platforms to the Métro station Gare d’Austerlitz to discover how soundscapes change over time.

These are sounds I recorded on the Métro station platform in 2011 when the old, bone shaking, MF67 trains were running.

Métro Line 5 – Gare d’Austerlitz in 2011

And these are sounds I recorded this year from exactly the same place. The difference is that the old rolling stock has been replaced with the newer, more energy efficient, smoother running, much more comfortable, air-conditioned, MF01 trains.

Métro Line 5 – Gare d’Austerlitz in 2017

The old MF67 trains no longer ply Line 5 of the Paris Métro and their iconic sounds have gone forever. I believe that the everyday sounds that surround us are as much a part of our heritage as the magnificent buildings that grace this city and, although change is inevitable and often for the better, the sounds we lose in the process deserve to be preserved.

Just as the sounds on Métro Line 5 have changed so will the sounds in and around Gare d’Austerlitz as its renovation unfolds. And I will be there to capture the changing soundscape for posterity.

Défilé Aérien du 14 Juillet

IT’S THAT TIME OF YEAR again, mid-July, la Fête Nationale and one of the high points of my sound recording year: the défilé aérien du 14 juillet.

Le quatorze juillet is the French National Day, commemorating the 1790 Fete de la Federation held on the first anniversary of the storming of the Bastille on 14th July 1789.

Each year, La Fête Nationale is celebrated throughout France but the centerpiece event takes place in Paris with the défilé, the parade of military and civilian services, marching down the Champs Elysées to be reviewed by the Président de la République. The défilé aérien, or fly-past, is part of the parade.

This year, to mark the 100th anniversary of the entry of the United States into World War I, 145 US troops took part in the parade in the Champs Elysées with their President, Donald Trump looking on.

As a lifelong aviation enthusiast, the parade in the Champs Elysées and the presence of Donald Trump were of much less interest to me than the events in the air.

As a lifelong aviation enthusiast, the parade in the Champs Elysées and the presence of Donald Trump were of much less interest to me than the events in the air.

This year the défilé aérien was made up of 63 aircraft: 49 from the French air force, 6 from the French navy and 8 from the United States, all flying in close formation.

The Aircraft Fly-Past:

Nine Alphajets of la Patrouille de France, the French aerobatic display team, led the fly-past complete with their signature bleu – blanc – rouge smoke. Then, close behind, came six F-16 Fighting Falcons of the USAF Air Demonstration Squadron, the Thunderbirds, and two Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptors, single-seat, twin-engine, all-weather stealth tactical fighter aircraft developed for the USAF.

Created in 1953 and based at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, the Thunderbirds Squadron tours the United States and much of the world, performing aerobatic formation and solo flying in specially marked aircraft.

The US Thunderbirds and F-22 Raptors heading for the Champs Elysées

This was the first time I had seen either the Thunderbirds or the F-22 Raptor so I was able to tick yet more boxes in my ‘plane spotting’ list as well as adding their distinctive sounds to my Paris Soundscapes Archive.

Another first was to see not one but TWO Airbus A-400M Atlas military transport aircraft flying in formation. This multi-national, four-engine turboprop aircraft was designed by Airbus Defence and Space as a tactical airlifter with strategic capabilities which, along with its transport role, can also perform aerial refueling and medical evacuation. The first of these aircraft was delivered to the French Air Force in August 2013.

Two Airbus A400M Atlas aircraft heading for the Champs Elysées

A little over half an hour after the aircraft had passed, the helicopters hove into view, 29 of them representing the French Army, Air Force, Navy and civilian services all flying in close formation.

The Helicopter Fly-Past:

Note: It’s hard to record the sound of helicopters en masse without making them sound like a hive of insects!

The défilé aérien is an event I look forward to each year, not because of the display of military hardware and fighting power on display, but simply because I have always been fascinated by aircraft. I guess I’ve never lost that child like wonder of watching and listening to flying machines.

Here are some more of my iPhone pictures of this year’s défilé aérien:

Tourists and Pigeons

IT IS ESTIMATED THAT between 30,000 and 50,000 people visit the Cathedrale Notre-Dame de Paris every day. It’s not surprising then that the queue waiting to get into the cathedral is often longer than the cathedral itself.

The queue stretches across the Parvis Notre-Dame, the square in front of the cathedral, which was renamed Parvis Notre-Dame – Place Jean-Paul II in 2006 in honour of Pope Jean-Paul II who died the previous year.

The square is a magnet for tourists who, as well as visiting the cathedral, often queue up to have their photograph taken at a small octagonal bronze plaque surrounded by a circular stone embedded into the ground bearing the legend, ‘Point zéro des routes de France’.

As the legend suggests, this is point zero, the point from which all distances from Paris to the rest of France are measured.

Visitors to this spot might not know though that this was once the site of the infamous l’Echelle de Justice, the pillory before which the condemned, with bare head and feet and with a rope around their neck and a placard on their chest and back describing their crime, were require to kneel, publicly acknowledge their crime and seek absolution. It was here in March 1314 for example, that Jacques de Molay, Grand Master of the Templars, heard the Pope’s decree condemning him to be burned alive!

Tourists weary of standing in line to visit the cathedral or jostling to take a look at point zero often gravitate towards the side of the parvis closest to la Seine to feed, or to be swamped by, huge flocks of pigeons.

Tourists and Pigeons:

Unlike the Cathedrale Notre-Dame de Paris, or point zero, or even the fabulous Crypte Archeologique du Parvis Notre-Dame, which lies underneath the parvis, these sounds of tourists and pigeons may not feature in the tourist guide books, but for me at least they are some of the quintessential summer sounds of Paris.

Marche Pour la Fermature des Abattoirs

DURING MY TIME living in Paris I have witnessed and recorded countless street demonstrations, or manifestations as we call them here. Whether it’s the spectacle of one million people filling the streets in 2010 to oppose the then Président Nicolas Sarkozy’s pension reforms or a mere handful of people protesting about the implementation of some obscure local byelaw, people here are not shy when it comes to taking to the streets to make their voices heard. Whatever the issue under protest, and whether I agree with it or not, I find the politics of the street endlessly fascinating.

Yesterday afternoon I was in the Beaubourg area of Paris, the area around the Centre Pompidou, recording street musicians. Having made several recordings, I headed off to a café for much needed refreshment and a sit down, but on the way I came upon a manifestation progressing along rue Beaubourg.

I discovered that this was an animal rights protest under the ‘Marche Pour la Fermature des Abattoirs’ banner, a march aimed at closing down abattoirs. I also discovered that this march was not confined to Paris; similar marches are taking place across the world this weekend.

Marche Pour la Fermature des Abattoirs:

Marche Pour la Fermature des Abattoirs:

As you can hear, the protestors’ vocal theme centred on the chant, ‘Fermons les Abattoirs’, close the abattoirs, a theme supported by leaflets with the message:

It’s time to claim loud and clear the abolition of slavery of all the animals, the abolition of the practices which cause them the biggest wrongs: their breeding, their fishing and their slaughter.

Every year in the world, 60 billion land animals and more than 1000 billion aquatic animals are killed without necessity, which means that 164 million land animals and more than 2,74 billion aquatic animals are killed every day.

This was a large, well-organised, enthusiastic and peaceful march with a wide cross-section of people taking to the street to express their point of view. Which brings me back to what I said at the beginning: whatever the protest, I find the politics of the street endlessly fascinating.

A Fifteenth Century Parisian Soundscape

I SPEND A GOOD PART my time recording and archiving the soundscapes of Paris. As fascinating as the contemporary soundscapes of this city are though, I am always thinking about what the city might have sounded like in the past when sounds were impossible to capture and to replay.

It was only towards the end of the nineteenth century that it became possible to record sound and well into the twentieth century before attention turned towards recording urban soundscapes. Before that, our only source for what our towns and cities might have sounded like is to be found in literature – the written accounts of the sounds people heard.

The American writer, John Sanderson, for example arrived in Paris for the first time in July 1835 …

“All things of this earth seek, at one time or another, repose – all but the noise of Paris. The waves of the sea are sometimes still, but the chaos of these streets is perpetual from generation to generation; it is the noise that never dies.”

John Sanderson, Sketches of Paris: In Familiar Letters to His Friends (1838)

Clearly, John Sanderson wasn’t impressed with what he found. But contrast that with a description of a much earlier Paris.

In Chapter 2 of Book Three of his novel, Notre-Dame de Paris, also known as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, Victor Hugo offers us a Bird’s Eye View of Paris in which he describes in fascinating detail the visual landscape of fifteenth century Paris from the top of the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris.

A Modern Day View from the Top of the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris.

Image via Wikipedia

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame was published in 1831 and it is clear in the novel that Victor Hugo was lamenting how the city had changed. About the Cathedral for example he says:

“The church of Notre-Dame de Paris is still no doubt, a majestic and sublime edifice. But, beautiful as it has been preserved in growing old, it is difficult not to sigh, not to wax indignant, before the numberless degradations and mutilations which time and men have both caused the venerable monument to suffer, without respect for Charlemagne, who laid its first stone, or for Philip Augustus, who laid the last.”

But it is when it comes to the sounds of fifteenth century Paris that Hugo is at his most eloquent.

“And if you wish to receive of the ancient city an impression with which the modern one can no longer furnish you, climb – on the morning of some grand festival, beneath the rising sun of Easter or of Pentecost – climb upon some elevated point, whence you command the entire capital; and be present at the wakening of the chimes. Behold, at a signal given from heaven, for it is the sun which gives it, all those churches quiver simultaneously. First come scattered strokes, running from one church to another, as when musicians give warning that they are about to begin. Then, all at once, behold! – for it seems at times, as though the ear also possessed a sight of its own,—behold, rising from each bell tower, something like a column of sound, a cloud of harmony. First, the vibration of each bell mounts straight upwards, pure and, so to speak, isolated from the others, into the splendid morning sky; then, little by little, as they swell they melt together, mingle, are lost in each other, and amalgamate in a magnificent concert. It is no longer anything but a mass of sonorous vibrations incessantly sent forth from the numerous belfries; floats, undulates, bounds, whirls over the city, and prolongs far beyond the horizon the deafening circle of its oscillations.

Nevertheless, this sea of harmony is not a chaos; great and profound as it is, it has not lost its transparency; you behold the windings of each group of notes which escapes from the belfries. You can follow the dialogue, by turns grave and shrill, of the treble and the bass; you can see the octaves leap from one tower to another; you watch them spring forth, winged, light, and whistling, from the silver bell, to fall, broken and limping from the bell of wood; you admire in their midst the rich gamut which incessantly ascends and re-ascends the seven bells of Saint-Eustache; you see light and rapid notes running across it, executing three or four luminous zigzags, and vanishing like flashes of lightning. Yonder is the Abbey of Saint-Martin, a shrill, cracked singer; here the gruff and gloomy voice of the Bastille; at the other end, the great tower of the Louvre, with its bass. The royal chime of the palace scatters on all sides, and without relaxation, resplendent trills, upon which fall, at regular intervals, the heavy strokes from the belfry of Notre-Dame, which makes them sparkle like the anvil under the hammer. At intervals you behold the passage of sounds of all forms which come from the triple peal of Saint-Germaine des Prés. Then, again, from time to time, this mass of sublime noises opens and gives passage to the beats of the Ave Maria, which bursts forth and sparkles like an aigrette of stars. Below, in the very depths of the concert, you confusedly distinguish the interior chanting of the churches, which exhales through the vibrating pores of their vaulted roofs.

Assuredly, this is an opera, which it is worth the trouble of listening to. Ordinarily, the noise which escapes from Paris by day is the city speaking; by night, it is the city breathing; in this case, it is the city singing. Lend an ear, then, to this concert of bell towers; spread over all the murmur of half a million men, the eternal plaint of the river, the infinite breathings of the wind, the grave and distant quartette of the four forests arranged upon the hills, on the horizon, like immense stacks of organ pipes; extinguish, as in a half shade, all that is too hoarse and too shrill about the central chime, and say whether you know anything in the world more rich and joyful, more golden, more dazzling, than this tumult of bells and chimes;—than this furnace of music,—than these ten thousand brazen voices chanting simultaneously in the flutes of stone, three hundred feet high,—than this city which is no longer anything but an orchestra,—than this symphony which produces the noise of a tempest.”

In articles for this blog I always include a sound, or sounds, of Paris that I’ve recorded, to which I add words and pictures to give the sounds an historical, social or cultural context. On this occasion, any sounds I could add would be quite superfluous to the words of Victor Hugo and the magnificent soundscape he describes.

I suggest you just relax, read Hugo’s words and, as he says, “Lend an ear, then, to this concert … this symphony which produces the noise of a tempest”.