End of the Line: La Défense – Grande Arche: Part 1

THE ‘END OF THE LINE’ STRAND in my Paris Soundscapes Archive is dedicated to the sounds I capture in and around each terminus station on the Paris Métro system. From time to time I share the atmosphere of some of these terminus stations and their surroundings on this blog.

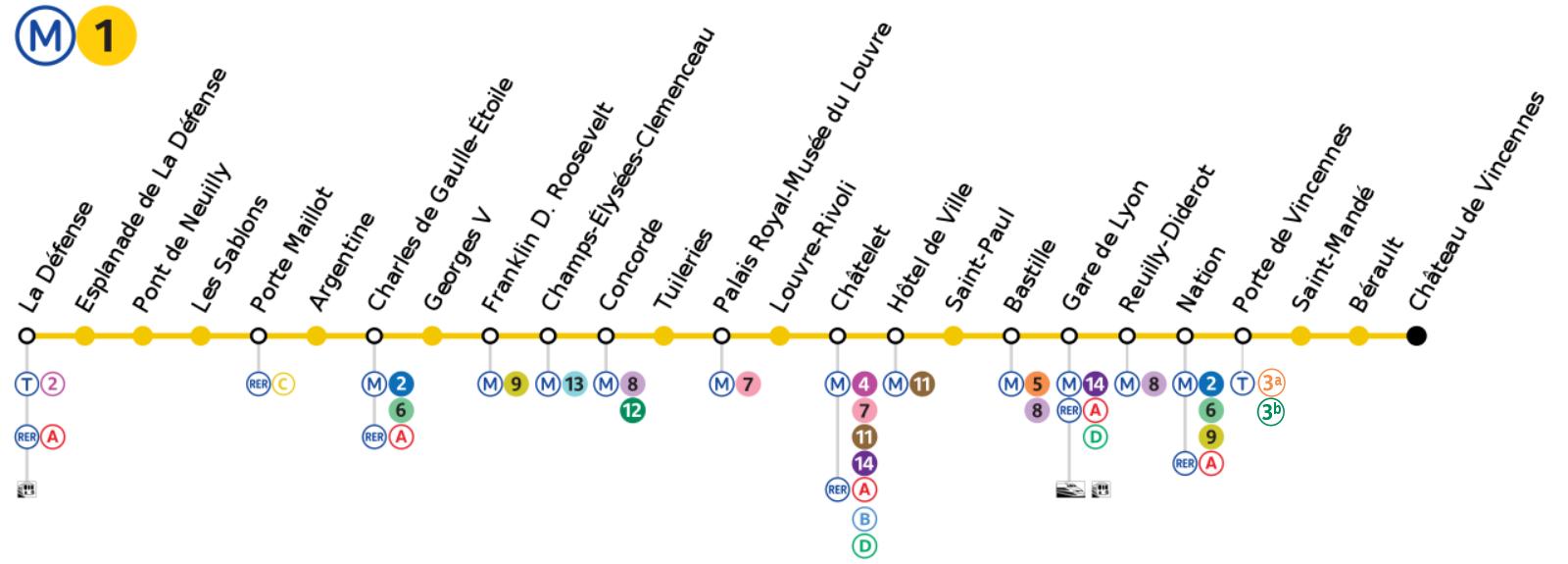

In previous ‘End of the Line’ posts I’ve explored the sounds in and around the Métro station Les Courtilles, the branch of Paris Métro Line 13 terminating in the northwest of Paris, and the sounds in and around Métro station Château de Vincennes, the easterly terminus of Paris Métro Line 1. Now I’m going to explore the sounds in and around the Métro station La Défense – Grande Arche, the westerly terminus of Métro Line 1.

However, to make this ‘End of the Line’ segment more manageable I will divide it into two parts. Today’s post, Part 1, explores inside La Défense – Grande Arche station and the next post, Part 2, will explore the sounds around the station in what is said to be Europe’s largest purpose-built business district containing most of the Paris urban area’s tallest high-rise buildings.

La Défense looking to the West

Because it serves the largest business district in the Paris region, La Défense – Grande Arche is a multi-functional transport hub. Not only is it home to the western terminus of Métro Line 1, it also houses a Transilien suburban train station, an RER station, a tram station and a bus station, all designed principally to handle the huge number of commuters who travel to and from work in La Défense each day.

La Défense – Grande Arche: The main concourse

The business district of La Défense is so big that it actually has two Métro stations. Esplanade de la Défense is the first of these so it was approaching here on my way to La Défense – Grande Arche that I began my sonic exploration.

Exploring La Défense – Grande Arche station in sound:

Opened on 19th July 1900, Métro Line 1 is the oldest line on the Paris Métro network. Built by the one-armed railway engineer Fulgence Bienvenüe, to connect various sites of the 1900 Exposition Universelle, the original line comprised eighteen stations between Porte Maillot and Porte de Vincennes. In 1934, the line was extended to the east from Porte de Vincennes to Chateau de Vincennes and in 1937 it was extended to the west from Porte Maillot to Pont de Neuilly. In 1992, Line 1 was extended again to the west from Pont de Neuilly to La Défense. In 2007, work began to automate Line 1 and on 15th December 2012 a fully automatic service was introduced. Today the 16.5 km Métro Line 1 is the most utilised line on the Paris Métro network handling over 600,000 passengers per day.

Arriving at the La Défense – Grande Arche terminus, I alighted and made my way up to the cavernous station concourse. This used to be a dingy, inhospitable place but a recent coat of paint has brightened it up a bit and now, the usual suspects cater for the commuters.

From the main concourse I headed off to explore the tram station, home to Tram Line T2.

Tram Line T2, linking the south-west suburbs of Paris with La Défense, began operating in 1997. The tramway was built on the former train line thus making it independent from the road. An extension In 2009 added five more stations towards the south, extending to Port de Versailles and in November 2012, another 4.2 km northern extension beyond La Défense to Bezons added a further seven stations.

The extensions to Tram Line 2 are part of a larger scheme in the Île-de-France aiming to increase connectivity of the suburbs by creating up to 70km of bus and tramways around Paris.

The Transilien suburban trains operate from platforms adjacent to but separated from the tram platforms.

While the public address announcements in the main station concourse are almost unintelligible, those in the tram station are much better – even if they do seem to appear end-to-end.

From the tram station I went back to the concourse and on to the RER station and RER Line A.

With more than one million passengers a day, RER Line A is the busiest Parisian urban rail line.

With the section of the line running through the city centre closed each summer for maintenance and construction work, much to the dismay of commuters, and with the line badly affected by alerts for suspect packages, which have doubled in the last year, it’s hardly surprising that, according to a 2017 survey by transport authorities in the greater Paris region, trains on RER Line A run on time only 85.3% of the time. Add to that grossly overcrowded trains and the occasional strike and RER Line A can sometimes be a challenge.

Despite the introduction of advanced traffic control systems that enable extremely short spacing between trains during rush hour (under 90 seconds in stations, under 2 minutes in tunnels) together with several upgrades in rolling stock, ever-increasing traffic volume and imminent saturation continues to blight the line.

Still, it’s not the worst performing RER line. According to the 2017 survey, that accolade goes to RER Line D.

The sounds of La Défense – Grande Arche presented in this post are a distillation of my original ninety minute recording now consigned to my Paris Soundscapes Archive but I hope they give you at least a flavour of the sonic tapestry hidden below the monumental Grande Arche de la Défense. In Part 2, I shall explore the sounds up on the surface.

Even with this extensive transport facility complete with its coffee shops and fast food outlets, travelling to and from La Défense during the rush hour each day can be a grim experience. I know, I did it for thirteen years!

Métro Station Liège and its Sounds

YOU CAN SEE THEM clearly from the train but since the automatic platform doors have been installed it’s now more difficult to view them from the platform, which is a shame because the decorative ceramic panels on the walls add a touch of class to Liège métro station.

Created by two Liège artists, Marie-Claire Van Vuchelen and Daniel Hicter, and installed in 1982, the ceramic panels depict some of the landscapes and monuments of the Province of Liège giving a very Belgian feel to this Paris métro station.

What is now métro station Liège was opened originally as métro station Berlin on 26th February 1911 as part of the Nord-Sud Company’s Line B from Saint-Lazare to Porte de Saint-Ouen.

Paris métro stations are usually named after people, places or events so the station took its original name from the rue de Berlin, one of the streets radiating out from the nearby Place de Europe in the 8th arrondissement. When the First World War broke out in 1914 and anti-German sentiment was particularly strong, the name of the street and consequently the name of the station was changed from Berlin, the capital of France’s enemy, to Liège, a city in the friendly neighbouring country of Belgium.

The ceramic panels are not the only unusual feature of this station.

As part of today’s Métro Line 13, the métro station Liège is located at the junction of the 8th and 9th arrondissements, about three hundred metres north of the mainline railway station, Gare Saint-Lazare. At this point, Line 13 runs directly under the rather narrow rue d’Amsterdam where it bisects rue de Liège.

This part of Line 13 was built using the ‘cut-and-cover’ method of construction. ‘Cut-and-cover’ is a simple method of construction for shallow tunnels where a trench is excavated and roofed over with an overhead support system strong enough to carry the load of what is to be built above the tunnel. The trench for this section of Line 13 was cut down from rue d’Amsterdam and because the street above was narrow so was trench forming the tunnel below. This meant that there was not enough room in the station to accommodate the usual two lines and two platforms opposite each other as is common in most Paris métro stations. Consequently, Liège is only one of two Paris métro stations to have offset platforms.

This rather poor picture culled from Wikipedia shows the offset platforms before the automatic platform doors were installed and it was still possible to see them.

The platform heading south (towards Châtillon – Montrouge) is located north of the junction of rue de Liège and rue d’Amsterdam above while the northbound platform (towards Asnières and Saint-Denis) is to the south of the junction. In each direction of travel, the trains stop at the first platform encountered.

This offset platform arrangement gives rise to a sonic curiosity. You can see from the picture that while the platforms are offset, both the northbound and the southbound tracks pass each platform. This means that this is the only station on the Paris Métro network where it is possible to hear trains regularly passing the platform without stopping. For example, if one is waiting at the northbound platform, the southbound train will pass without stopping and vice versa.

Stopping and passing trains in métro station Liège:

Another interesting sonic feature inside this station is the effect of the relatively narrow tunnel and its curved wall. The wall seems to both amplify the sounds of the trains while attenuating the ambient sounds between trains.

Note: I took these two pictures of the ceramic panels with my iPhone pressed against the glass of the closed automatic platform doors fully aware that at any moment what might seem like my suspicious behaviour could result in unpleasant consequences!

At the outbreak of World War Two, métro station Liège, like several other Paris métro stations, was closed for economy reasons. After the conflict, most of the stations reopened but some of them, including Liège, didn’t and they became known as the stations fantômes, or ghost stations. Liège station eventually reopened in 1968 but only with a limited service and it wasn’t until as late as December 2006 that the station began to operate a full service.

One of the features of Liège métro station is the platform office to be found on each platform. I have visions of them once being occupied by an authoritarian early twentieth-century stationmaster or maybe an equally authoritarian ticket collector. In fact, they date from the twenty-first century renovation of the station.

Of all the features of this station though it is the decorative ceramic panels made up of 6,576 ceramic tiles that dominate. There are eighteen panels altogether, nine on each platform.

On one platform are those designed by Daniel Hicter, each of which has a blue tone:

– Coo, dans la vallée de l’Amblève

– Les premières neiges en Fagnes

– Le barrage de La Gileppe

– L’Eglise romane de Momalle

– Le village de Limbourg

– Le château de Jehay-Bodegnée

– Le circuit automobile de Spa-Francorchamps

– Le château de Chokier-sur-Meuse

– Le Palais des Princes-Evêques de Liège

And on the other platform are those by Marie-Claire Van Vuchelen, each with a brown-ochre tone:

– La vallée du Hoyoux à Modave

– La vallée de la Vesdre à Nessonvaux

– Le Château de Wégimont à Soumagne

– Le Perron de Liège

– L’Hôtel de Ville de Verviers

– Le pont, la collégiale et la citadelle de Huy

– La maison Curtius à Liège

– Le Château de Colonster dans la Vallée de l’Ourthe

– L’Hôtel de Ville de Visé

If you’re travelling on Line 13 of the Paris Métro, it’s well worth getting off at Liège to have a look at these ceramic panels – even if you do now have to peer through the glass panels of the automatic platform doors.

À la Mémoire d’Edith Piaf

I SPEND QUITE A LOT of time in churches, especially Parisian churches.

I am interested in church architecture, I’m fascinated by the history of individual churches and I enjoy exploring the sounds of churches. One strand of my Paris Soundscapes Archive is dedicated to the sounds of Parisian churches. I have a particular interest in the work of the master organ builder, Aristide Cavaillé-Coll, and the organs he built for Parisian churches and while I’ve made many recordings of these Cavaillé-Coll organs I also record the ambient sounds in churches, especially when they’re empty. In my experience, there are no silent churches in Paris: even without services taking place, without the organ playing and with no people, there are still sounds. It’s as though the very fabric of each church speaks to the attentive listener.

Apart from weddings and funerals (more of the latter than the former these days unfortunately) I seldom go to churches other than to explore their architecture, history and sounds. Imagine my surprise then when, thanks to a confluence of interests, I found myself, despite not being of the Roman Catholic persuasion, attending a Roman Catholic mass yesterday morning.

The twin-spired Église Saint Jean-Baptiste de Belleville has been on my Parisian church exploration ‘to-do’ list for some time. It was built between 1854 and 1859 in the neogothic style by the architect Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus, an expert in the restoration and recreation of medieval architecture, and it replaces a chapel built in 1543 and the first Saint-Jean-Baptiste church dating from 1635.

Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Belleville was one of the first churches in Paris to be built in the neogothic style, which in itself was a good enough reason to visit it, but the fact that it also has a two-keyboard Cavaillé-Coll organ dating from 1863 was an added attraction.

One of the things I knew about the church was that Edith Piaf, the French cabaret singer, songwriter and actress, was baptised here on the 15th December 1917.

It was this confluence of interests: the neogothic l’église Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Belleville, a Cavaillé-Coll organ, my enthusiasm for Edith Piaf, in my view one of the greatest performers of the 20th century, together with the sound-rich environment of Belleville that brought me to this place yesterday morning where, to commemorate the 54th anniversary of her death, a Messe à la memoire d’Edith Piaf took place in the church supported by Les Amis d’Edith Piaf.

During the Mass the organ played and, of course, I had to record it for my archive. From my recording I’ve produced the following sound piece of some of the music played, which illustrates some of the voices and textures of the Cavaillé-Coll organ and gives a flavour of the Mass itself.

The Cavaillé-Coll organ of the Église Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Belleville:

The piece opens with the full-throated Entrée. The tone changes for the next piece, the music for the Offertoire. Then comes the music for the Communion, an improvisation on “Non, je ne regrette rien”, a French song originally composed by Charles Dumont, with lyrics by Michel Vaucaire, always associated with Edith Piaf’s 1959 recording of it. The Sortie comprises a short organ piece followed by the lady herself singing “Hymne à l’amour” for which she wrote the words and Marguerite Monnot the music.

The organ was played by Laurent Jochum, organiste titulaire des grandes orgues Cavaillé-Coll de l’église Saint-Jean Baptiste de Belleville et de l’orgue de la Chapelle du collège et lycée Saint-Louis de Gonzague à Paris.

I am old enough to remember listening to Edith Piaf on the radio and I can remember her funeral bringing Paris to a standstill being headline news. For some of her short life she lived just round the corner from where I live now.

Sitting in the church yesterday morning next to the font where she was baptised and with her voice echoing around the church, it seemed ironic that, because of her lifestyle, the Catholic Church denied her a funeral mass when she died – they branded her ‘a categorical sinner’. Instead, her coffin was carried through the streets of Paris to be buried at the Père Lachaise cemetery with only a token blessing.

It was only on 10th October 2013, fifty years after her death, that the Roman Catholic Church gave her a memorial Mass in l’église Saint Jean-Baptiste in the parish in which she was born.

I don’t propose to document the life of Edith Piaf here; a quick search of Edith Piaf on Google will tell you much of what you need to know about her.

What I can say is that it is said she was born on the steps of N° 72 rue de Belleville on 19th December 1915. Her birth was registered at the Hôpital Tenon, next to what is now Place Edith Piaf in the 20th arrondissement, under the name Edith Giovanna Gassion.

In 2013, a statue of Edith Piaf, known as l’Hommage à Piaf, created by the French sculptor, Lisbeth Delisle, was inaugurated in the Place Edith Piaf.

Following yesterday’s Mass in Belleville I went to Place Edith Piaf to take in the atmosphere. I found a street market in full swing with some sounds that Edith herself might have been familiar with.

Sounds in Place Edith Piaf:

I couldn’t possibly end my own hommage to Edith Piaf yesterday without visiting her grave in the Cimetière du Père Lachaise.

She died on 10th October 1963 at the age of 47. Denied a funeral mass by the Catholic Church, some 10,000 people came to the cemetery to witness the interment of La Môme Piaf (‘The Little Sparrow’).

Edith Piaf was interred in the same grave as her father, Louis-Alphonse Gassion, and Theophanis Lamboukas, (Théo Sarapo), whom she married in 1962. She is buried next to her daughter, Marcelle, who died of meningitis at the age of two.

Of the 70,000 graves in the Cimetière Père Lachaise, Edith Piaf’s remains one of the most visited.

From the sounds of the Cavaillé-Coll organ in l’église Saint Jean-Baptiste and the bustling sounds of the street market in Place Edith Piaf, I couldn’t leave the cemetery without recording the sounds of the relative stillness surrounding Edith Piaf’s grave.

Like the fabric of an empty church, cemeteries speak to the attentive listener.

The sounds around Edith Piaf’s grave:

“Every damn thing you do in this life, you have to pay for.”

Edith Piaf

“Je ne me repends pas de m’être livrée à l’amour.”

(“I do not repent having given myself up to love.”)

Sainte Thérèse de Lisieux

End of the Line – Château de Vincennes

THE ‘END OF THE LINE’ STRAND in my Paris Soundscapes Archive is dedicated to the sounds I capture in and around each terminus station on the Paris Métro system. From time to time I will share the atmosphere of some of these terminus stations and their surroundings on this blog.

In my last ‘End of the Line’ post I explored in and around the Métro station Les Courtilles, the branch of Paris Métro Line 13 terminating in the northwest of Paris. Today, I will share with you my exploration in and around Métro station Château de Vincennes, the easterly terminus of Paris Métro Line 1.

Opened in 1900, Métro Line 1 was the first Paris Métro line to be opened although it was shorter then than it is now. Today, it runs for 16.5 km from La Défense in the west of the city to Château de Vincennes in the east and well over half a million people use it each day making it the busiest line on the Paris Métro system.

In 2007, work began to convert the line from being manually driven to becoming a fully automatic, driverless, operation. The work was completed in 2011 and involved the introduction of new MP 05 rolling stock and the erection of platform edge doors in all stations.

I recorded my arrival at Château de Vincennes station, a ride up a creaky escalator, a walk across the station concourse, up another escalator and out into the street above.

Arrival at Château de Vincennes:

Both the name of the station and a display in the station concourse give us a clue to at least one thing we might find outside.

Vincennes is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the eastern suburbs of Paris. As well as its famous castle, the Château de Vincennes, once home to French Kings, Vincennes is also known for the adjacent 995 hectare (2,459 acres) Bois de Vincennes, the largest public park in Paris, a zoo, the Paris Zoological Park, a botanical garden, the Parc Floral de Paris, and a large military fort once used as a proving ground for French armaments. Vincennes is also home to the Service Historique de la Défense, which holds the archival records of the French Armed Forces.

A short walk from the Métro station I discovered the Cours Marigny, a promenade between the Château de Vincennes and the Hôtel de Ville undergoing a makeover due to be completed in the Spring of 2018.

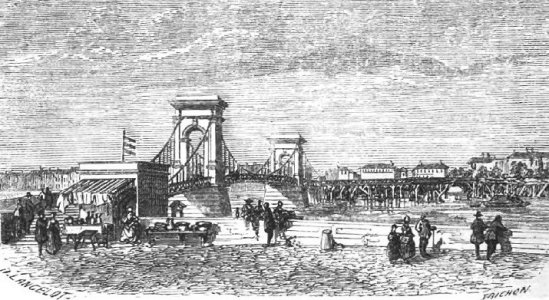

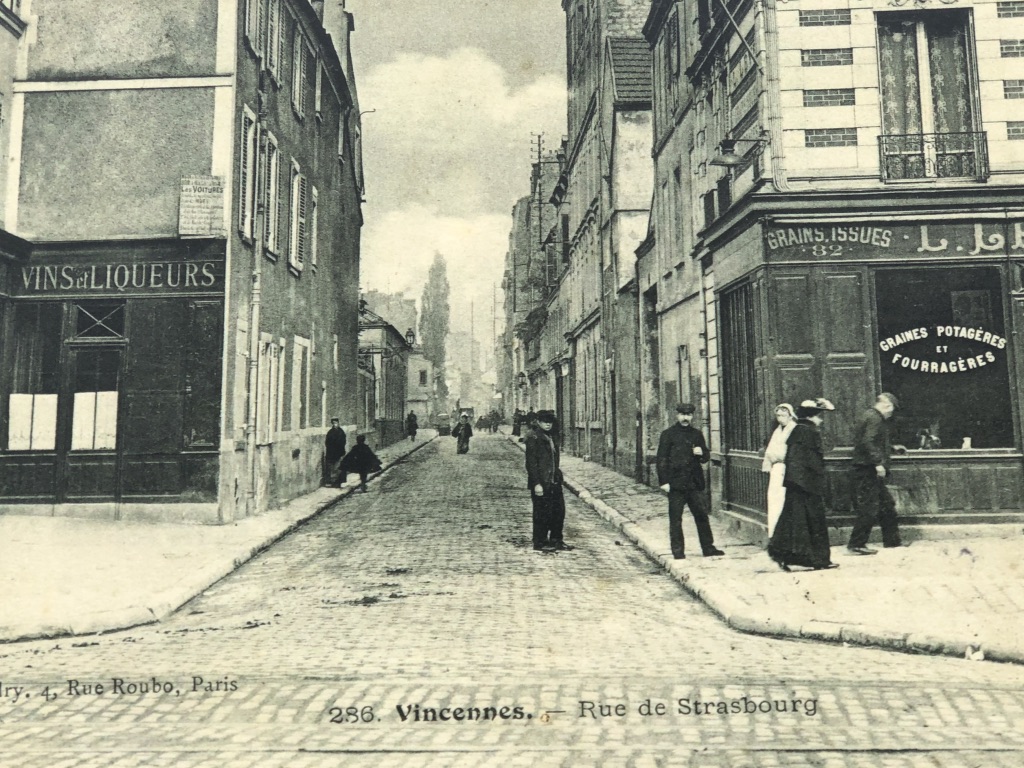

In the town square I found a display of old photographs showing Vincennes as it once was.

But in Vincennes, town and crown sit cheek by jowl so the château is never far away.

The Château de Vincennes is a massive former French royal fortress, which originated as a hunting lodge constructed for Louis VII around 1150 in the forest of Vincennes. In the 13th century, Philip Augustus and Louis IX, King of France from 1226 until his death during the eighth crusade in 1270, erected a more substantial manor.

King Louis IX – Saint Louis, outside the Château de Vincennes

By the 14th century, the Château de Vincennes had expanded and outgrown its original site. With the outbreak of the Hundred Years War, it became as much a fortress as a family home. Philip VI added a donjon, or fortified keep, which at 52 meters high was the tallest medieval fortified structure in Europe at the time. The grand rectangular circuit of walls was completed in about 1410.

The donjon served as a residence for the royal family and its buildings are known to have once held the library and personal study of Charles V. In 1422, seven years after his victory at Agincourt, Henry V of England died in the donjon from dysentery, which he had contracted during the siege of Meaux.

By the 18th century, the Château de Vincennes had ceased to become a practical fortress. Instead it became home to the Vincennes porcelain manufactory, precursor to the Sèvres porcelain factory, and the keep became a prison housing such distinguished guests as the Marquis de Sade, Diderot, and the French revolutionary, the Comte de Mirabeau,

Sounds around the Métro station Château de Vincennes :

To capture the ‘End of the Line’ atmosphere around the Métro station Château de Vincennes I recorded while sitting on a green bench alongside the wall and the moat on the western side of the château, close to one of the Métro entrances and even closer to the donjon and its bell tower. The sounds are the everyday sounds of this leafy part of Vincennes, including the chiming of the donjon bell.

In his book, Nairn’s Paris, a unique guide to Paris published in 1968, the British architectural critic, Ian Nairn, has a particular view about the Château de Vincennes:

“The château must be one of the most bad-tempered collections of buildings in the world, full of the prose of containment without any of the poetry of castellation. The vast medieval curtain-wall is opened out at the south end, towards the Bois, with grumpy classical buildings by Le Vau: on the north side there is the entrance tower, and brooding over the whole cross-grained mixture is the fourteenth-century donjon, which they say is the tallest in Europe; five huge storeys, surrounded by its own curtain-wall. Inside, the tall rooms, each heavily vaulted from a single pillar, give away nothing more than the facts of incarceration, if anything reinforced by the Gothic ribs and corbels that are familiar from less gloomy places. It is no illusion: Vincennes has a grim record and the tiny ill-light cells are still there to prove it.

[…]

One final view, the only soft thing at Vincennes: the eastern side of the moat, choked with big trees, Nature at last getting its own back on man. But the town that has grown up opposite this wicked uncle is as different as could be – a kind of French Aldershot. Vincennes has many barracks, some of them still inside the walls, and France has compulsory military service. Across the road from the château is a bus terminus, the end of a Métro, a line-up of cheerful cafés, and a considerable variety of, cheerful, cheap, not very good meals.”

Nairn’s Paris by Ian Nairn – Penguin Books (1968)

Just for clarification: For those not familiar with it, Aldershot, to which Ian Nairn refers, is a garrison town in the south of England, and France no longer has compulsory military service. The bus terminus, the end of the Métro and the line-up of cheerful cafés are still there and, although not as cheap as they were, some of the meals at least have improved!

Sounds In and Around L’Église Saint-Merri

IF YOU’VE READ Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables you will have read Hugo’s fictional account of the June Rebellion or the Paris Uprising of 1832, the last outbreak of violence linked with the July Revolution of 1830.

Général Jean Maximilien Lamarque had been a French commander during the Napoleonic Wars and had served with distinction in many of Napoleon’s campaigns. But following the July Revolution of 1830 he had become a leading critic of the new constitutional monarchy of Louis Philippe. In Les Misérables, Victor Hugo views Lamarque as the government’s champion of the poor. He says that Lamarque was “loved by the people because he accepted the chances the future offered, loved by the mob because he served the emperor well”. Hugo portrays Lamarque as an emblem of French pride and honour.

In 1832, a cholera epidemic spread across France and Lamarque fell victim to it. He died on 1st June. Because of his status as a Republican and Napoleonic war hero, his death provided the spark that led the revolutionaries to take to their barricades.

On the 5th and 6th June 1832, Paris saw two bloody days of rioting with the Société des amis du peuple, la Société des droits de l’homme, students, craftsmen and labourers playing a principal part. But as early as the evening of 5th the Army and the National Guard had begun to suppress the uprising. By the following day fierce fighting centered on the last remaining pocket of resistance in the Rue du Cloitre-Saint-Merri beside the Église Saint-Merri, but this too was finally suppressed.

Over the two days of the uprising some 800 people were killed or wounded.

Rue du Cloitre-Saint-Merri

The rue du Cloitre-Saint-Merri dates from the 12th century. It was originally called Rue de la Porte Saint-Merri, because it was next to l’Arche Saint-Merri, a 10th century gate through the second wall to encircle Paris.

By the 14th century, the street had become one of many streets in Paris noted for its prostitutes; at least it was until the parish priests of Saint-Merri demanded, not altogether successfully, that they be expelled.

Today, rue du Cloitre-Saint-Merri runs for 132 metres from rue du Renard to rue Saint-Martin. For much of its length it runs alongside the northern side of the Église Saint-Merri.

At its junction with rue Saint-Martin, the rue du Cloitre-Saint-Merri ends with a small square noted for its ever-changing street art.

It was around this small square that some of the bloodiest fighting of the Paris uprising took place, and it was here that I chose to sit on a bench partly to reflect on the events of 1832 and partly to absorb the elaborate 16th century gothic architecture of the Église Saint-Merri standing next to me.

Église Saint-Merri

For someone wired up like me it’s impossible not to contemplate history without conjuring up images of the sounds associated with that history. What would this place have sounded like I wondered in June 1832, or when the Église Saint-Merri was in its Middle-Ages pomp, or even when rue du Cloitre-Saint-Merri was a 14th century rue aux ribaudes?

Unfortunately, from my Parisian green bench my imagined historical sounds were overwhelmed by the contemporary sounds around me – 16th century stonemasons replaced by 21st century Chinese building contractors.

Sounds around l’ Église Saint-Merri:

If you make it to the end of this sound piece you will discover that at least a flicker of the Parisian revolutionary spirit still survives: a lone voice of protest is heard as the whining of the weapon of mass construction reappears.

Although the Église Saint-Merri we see today dates from the mid-16th century, its roots go much further back.

Tradition has it that Medericus, abbot of the Abbey of Saint-Martin d’Autun, came to live as a hermit in a hut near the Saint-Pierre-des-Bois oratory which stood on the site of the present church. He is said to have died in August 700 and was buried there. He was later canonised and renamed Saint-Médéric.

In 884, Goslin, the bishop of Paris, had Médéric’s remains exhumed and laid to rest in the Saint-Pierre-des-Bois oratory, which now became the Saint-Médéric chapel. It was at this time that Saint-Médéric became the patron saint of the Right Bank.

Over time, the name Médéric was contracted to Merri, which is why the Église Saint-Merri and the rue du Cloitre-Saint-Merri are so named.

Today, the remains of Saint-Médéric still rest in the crypt of the church.

In the early 10th century, a new church, Saint-Pierre-Saint-Merri, was built at the instigation of Eudes Le Fauconnier. Styled as a ‘Royal Officer’, it is possible that this was the same Eudes Le Fauconnier who took part in the defence Paris during the Viking siege in 885-86.

During the rebuilding of the church in the sixteenth century, the skeleton of a warrior was discovered together with boots of gilded leather and the inscription:

“Hic jacet vir bonæ memoriæ Odo Falconarius fundator hujus ecclesiæ”.

Which, based upon my schoolboy Latin, means something like:

“Here lies Eudes Le Fauconnier, of fond memory, founder of this church”.

The present day Église Saint-Merri was built between 1515 and 1612. The crypt, the nave and the aisles date from 1515-1520, the transept crossing from 1526-1530 and the choir and the apse were completed in 1552.

Some restoration work was carried out in the 18th century; some of the broken arches were repaired, the floor was covered with marble and the stained-glass windows were partly replaced by white glass.

During the French Revolution the church was closed for worship and was used to make saltpetre, one of the constituents of gunpowder. From 1797 to 1801, Theophilanthropists made it a “Temple of Commerce”. Theophilanthropists were a deistic society established in Paris during the period of the Directory aiming to institute in place of Christianity, which had been officially abolished, a new religion affirming belief in the existence of God, in the immortality of the soul, and in virtue.

The church was returned to the Catholic worship in 1803.

Sounds inside the Église Saint-Merri:

The northern aspect of the Église Saint-Merri and the bell tower

Image par Mbzt — Travail personnel, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13660170

The bell-tower was built with three floors in 1612 but, following a fire in 1871, it was reduced to two floors. This bell tower houses the oldest bell in Paris dating from 1331.

The Choir Organ

The Église Saint-Merri has two organs, a choir organ and a grand orgue de tribune.

The grand orgue de tribune

François de Heman built the tribune organ with its five turrets between 1647 and 1650 and the master carpenter Germain Pilon crafted the turret buffet in 1647.

The instrument was enlarged by François-Henri Clicquot in 1779, and then rebuilt from 1855 to 1857 by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll. Further work was carried out in 1947 by Victor Gonzalez.

Camille Saint-Saëns was the organist at the Église Saint-Merri from 1853 to1857.

My exploration of the sounds in and around the Église Saint-Merri took me from Medericus, a hermit living in a hut and subsequently canonised, to Eudes Le Fauconnier and the 9th century Viking siege of Paris, to the craftsmen of the 16th and 17th century, to the oldest bell in Paris, to a church used for making gunpowder and the bloody events of the Paris Uprising of 1832. And let’s not forget the medieval Parisian street with its ‘ladies of the night’ and the modern day Chinese builders.

Which goes to show that following contemporary sounds can lead in many different directions.

The Passage Molière and its Sounds

BECAUSE IT’S NEVER HAD a roof, the Passage Molière doesn’t qualify as one of the surviving Parisian passages couverts, the covered passageways built mainly in the first half of the nineteenth century. What the Passage Molière can claim though is that it predates all the one hundred and fifty original passages couverts.

Passage Molière from rue Quincampoix

The oldest Parisian passage couvert, the Passage des Panoramas, opened in 1799 whereas the Passage Molière dates back to 1791.

The Passage des Panoramas and the Passage Molière do have something in common though: both house a theatre. The Passage des Panoramas is one of the twenty surviving passages couverts and it is still home to the Théâtre des Variétés, while the Passage Molière is home to the Théâtre Molière from which the passage takes its name.

The Théâtre Molière was founded by the French actor, playwright, theatre director, businessman and revolutionary, Jean François Boursault-Malherbe. It opened on 18th June 1791 with a performance of Molière’s The Misanthrope, a satire about the hypocrisies of French aristocratic society and the flaws that all humans possess.

Unfortunately, the theatre was not a resounding success. It closed in August 1792 and then underwent several changes of management and several changes of name, although Boursault retained the ownership. The theatre became variously known as the Théâtre des Sans-culottes, Théâtre de la rue Saint-Martin, Théâtre des Artistes en société, Théâtre des Amis des arts et de l’Opéra-Comique and Théâtre des Variétés nationales et étrangères.

The theatre’s fortunes recovered a little at the turn of the century thanks to several notable actors being persuaded to perform there including Thomas Sheridan, but in 1807 it was closed again and became a hall for concerts, banquets and balls.

The theatre opened yet again in 1831 but in the revolutionary climate of 1848 it was occupied by the Club patriotique du 7e arrondissement for political meetings and thereafter was abandoned and fell into oblivion for more than a century.

Eventually, the City of Paris authorities stepped in and restored the theatre back to its original eighteenth century architecture. Today, the theatre forms part of the Maison de la Poésie – Scène littéraire in the Passage Molière.

Founded in 1983, La Maison de la Poésie was created for the creation and dissemination of, and events about, contemporary poetry.

Sounds in the Passage Molière:

Maison de la Poésie – Scène litteraire

The Passage Molière runs in an east – west direction from 157 rue Saint-Martin to 82 rue Quincampoix. At fifty metres long it cuts through blocks of buildings with each end covered where it passes under the buildings.

Like the Théâtre Molière, the passage has had several names. During the French Revolution it became the Passage des Sans-Culottes and then the Passage des Nourrices before reverting back to Passage Molière.

I recorded the sounds in the Passage Molière from outside the Maison de la Poésie and the restored Théâtre Molière with rue Saint-Martin to my left and rue Quincampoix to my right. The passage is a relatively quiet oasis amidst the more strident sounds of the surrounding neighbourhood so all I had to do was to give the sounds time to speak and tell their own story.

Walking through the Passage Molière, the attentive observer may notice that the building numbers do not follow the Parisian street numbering convention of even numbers on one side and odd numbers on the other with the lower numbers progressing to the higher numbers in the same direction.

In the Passage Molière, the numbers progress in an anti-clockwise direction. Starting on the right side of the passage at its eastern end, the numbers increase sequentially heading west and then from the western end, the numbers continue sequentially heading east.

Passage Molière from rue Saint-Martin