End of the Line: La Défense – Grande Arche: Part 1

THE ‘END OF THE LINE’ STRAND in my Paris Soundscapes Archive is dedicated to the sounds I capture in and around each terminus station on the Paris Métro system. From time to time I share the atmosphere of some of these terminus stations and their surroundings on this blog.

In previous ‘End of the Line’ posts I’ve explored the sounds in and around the Métro station Les Courtilles, the branch of Paris Métro Line 13 terminating in the northwest of Paris, and the sounds in and around Métro station Château de Vincennes, the easterly terminus of Paris Métro Line 1. Now I’m going to explore the sounds in and around the Métro station La Défense – Grande Arche, the westerly terminus of Métro Line 1.

However, to make this ‘End of the Line’ segment more manageable I will divide it into two parts. Today’s post, Part 1, explores inside La Défense – Grande Arche station and the next post, Part 2, will explore the sounds around the station in what is said to be Europe’s largest purpose-built business district containing most of the Paris urban area’s tallest high-rise buildings.

La Défense looking to the West

Because it serves the largest business district in the Paris region, La Défense – Grande Arche is a multi-functional transport hub. Not only is it home to the western terminus of Métro Line 1, it also houses a Transilien suburban train station, an RER station, a tram station and a bus station, all designed principally to handle the huge number of commuters who travel to and from work in La Défense each day.

La Défense – Grande Arche: The main concourse

The business district of La Défense is so big that it actually has two Métro stations. Esplanade de la Défense is the first of these so it was approaching here on my way to La Défense – Grande Arche that I began my sonic exploration.

Exploring La Défense – Grande Arche station in sound:

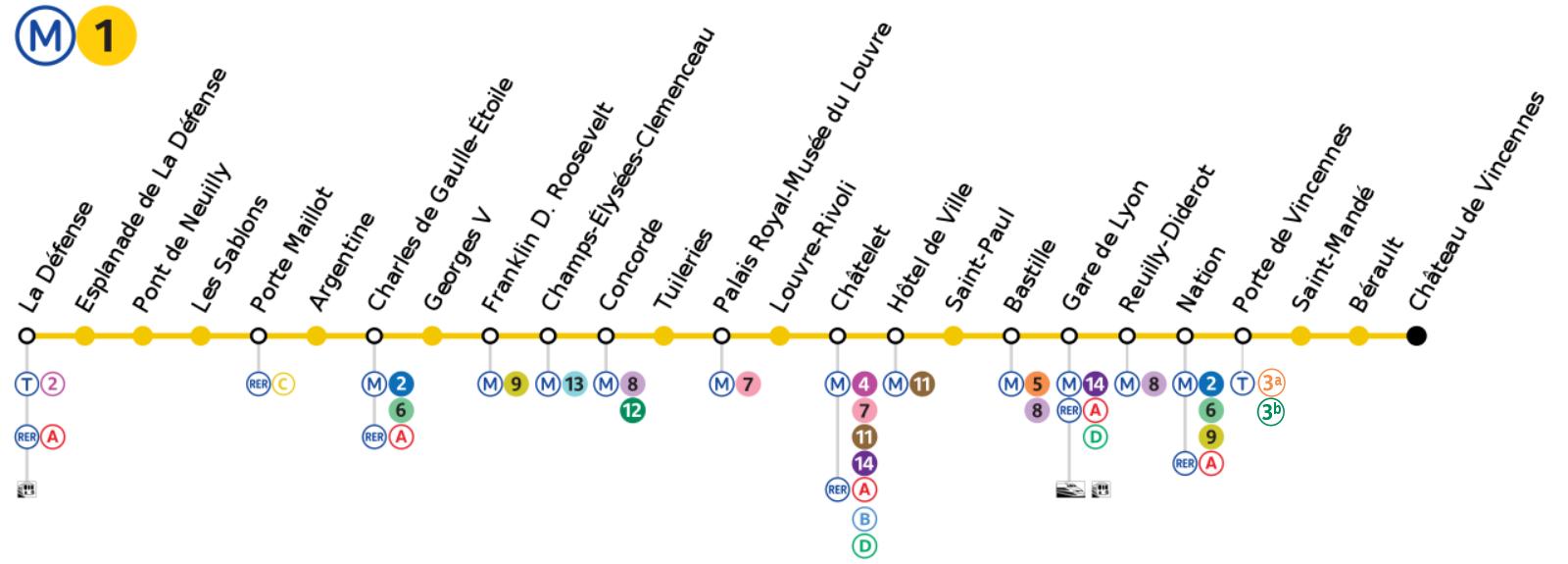

Opened on 19th July 1900, Métro Line 1 is the oldest line on the Paris Métro network. Built by the one-armed railway engineer Fulgence Bienvenüe, to connect various sites of the 1900 Exposition Universelle, the original line comprised eighteen stations between Porte Maillot and Porte de Vincennes. In 1934, the line was extended to the east from Porte de Vincennes to Chateau de Vincennes and in 1937 it was extended to the west from Porte Maillot to Pont de Neuilly. In 1992, Line 1 was extended again to the west from Pont de Neuilly to La Défense. In 2007, work began to automate Line 1 and on 15th December 2012 a fully automatic service was introduced. Today the 16.5 km Métro Line 1 is the most utilised line on the Paris Métro network handling over 600,000 passengers per day.

Arriving at the La Défense – Grande Arche terminus, I alighted and made my way up to the cavernous station concourse. This used to be a dingy, inhospitable place but a recent coat of paint has brightened it up a bit and now, the usual suspects cater for the commuters.

From the main concourse I headed off to explore the tram station, home to Tram Line T2.

Tram Line T2, linking the south-west suburbs of Paris with La Défense, began operating in 1997. The tramway was built on the former train line thus making it independent from the road. An extension In 2009 added five more stations towards the south, extending to Port de Versailles and in November 2012, another 4.2 km northern extension beyond La Défense to Bezons added a further seven stations.

The extensions to Tram Line 2 are part of a larger scheme in the Île-de-France aiming to increase connectivity of the suburbs by creating up to 70km of bus and tramways around Paris.

The Transilien suburban trains operate from platforms adjacent to but separated from the tram platforms.

While the public address announcements in the main station concourse are almost unintelligible, those in the tram station are much better – even if they do seem to appear end-to-end.

From the tram station I went back to the concourse and on to the RER station and RER Line A.

With more than one million passengers a day, RER Line A is the busiest Parisian urban rail line.

With the section of the line running through the city centre closed each summer for maintenance and construction work, much to the dismay of commuters, and with the line badly affected by alerts for suspect packages, which have doubled in the last year, it’s hardly surprising that, according to a 2017 survey by transport authorities in the greater Paris region, trains on RER Line A run on time only 85.3% of the time. Add to that grossly overcrowded trains and the occasional strike and RER Line A can sometimes be a challenge.

Despite the introduction of advanced traffic control systems that enable extremely short spacing between trains during rush hour (under 90 seconds in stations, under 2 minutes in tunnels) together with several upgrades in rolling stock, ever-increasing traffic volume and imminent saturation continues to blight the line.

Still, it’s not the worst performing RER line. According to the 2017 survey, that accolade goes to RER Line D.

The sounds of La Défense – Grande Arche presented in this post are a distillation of my original ninety minute recording now consigned to my Paris Soundscapes Archive but I hope they give you at least a flavour of the sonic tapestry hidden below the monumental Grande Arche de la Défense. In Part 2, I shall explore the sounds up on the surface.

Even with this extensive transport facility complete with its coffee shops and fast food outlets, travelling to and from La Défense during the rush hour each day can be a grim experience. I know, I did it for thirteen years!

Métro Station Liège and its Sounds

YOU CAN SEE THEM clearly from the train but since the automatic platform doors have been installed it’s now more difficult to view them from the platform, which is a shame because the decorative ceramic panels on the walls add a touch of class to Liège métro station.

Created by two Liège artists, Marie-Claire Van Vuchelen and Daniel Hicter, and installed in 1982, the ceramic panels depict some of the landscapes and monuments of the Province of Liège giving a very Belgian feel to this Paris métro station.

What is now métro station Liège was opened originally as métro station Berlin on 26th February 1911 as part of the Nord-Sud Company’s Line B from Saint-Lazare to Porte de Saint-Ouen.

Paris métro stations are usually named after people, places or events so the station took its original name from the rue de Berlin, one of the streets radiating out from the nearby Place de Europe in the 8th arrondissement. When the First World War broke out in 1914 and anti-German sentiment was particularly strong, the name of the street and consequently the name of the station was changed from Berlin, the capital of France’s enemy, to Liège, a city in the friendly neighbouring country of Belgium.

The ceramic panels are not the only unusual feature of this station.

As part of today’s Métro Line 13, the métro station Liège is located at the junction of the 8th and 9th arrondissements, about three hundred metres north of the mainline railway station, Gare Saint-Lazare. At this point, Line 13 runs directly under the rather narrow rue d’Amsterdam where it bisects rue de Liège.

This part of Line 13 was built using the ‘cut-and-cover’ method of construction. ‘Cut-and-cover’ is a simple method of construction for shallow tunnels where a trench is excavated and roofed over with an overhead support system strong enough to carry the load of what is to be built above the tunnel. The trench for this section of Line 13 was cut down from rue d’Amsterdam and because the street above was narrow so was trench forming the tunnel below. This meant that there was not enough room in the station to accommodate the usual two lines and two platforms opposite each other as is common in most Paris métro stations. Consequently, Liège is only one of two Paris métro stations to have offset platforms.

This rather poor picture culled from Wikipedia shows the offset platforms before the automatic platform doors were installed and it was still possible to see them.

The platform heading south (towards Châtillon – Montrouge) is located north of the junction of rue de Liège and rue d’Amsterdam above while the northbound platform (towards Asnières and Saint-Denis) is to the south of the junction. In each direction of travel, the trains stop at the first platform encountered.

This offset platform arrangement gives rise to a sonic curiosity. You can see from the picture that while the platforms are offset, both the northbound and the southbound tracks pass each platform. This means that this is the only station on the Paris Métro network where it is possible to hear trains regularly passing the platform without stopping. For example, if one is waiting at the northbound platform, the southbound train will pass without stopping and vice versa.

Stopping and passing trains in métro station Liège:

Another interesting sonic feature inside this station is the effect of the relatively narrow tunnel and its curved wall. The wall seems to both amplify the sounds of the trains while attenuating the ambient sounds between trains.

Note: I took these two pictures of the ceramic panels with my iPhone pressed against the glass of the closed automatic platform doors fully aware that at any moment what might seem like my suspicious behaviour could result in unpleasant consequences!

At the outbreak of World War Two, métro station Liège, like several other Paris métro stations, was closed for economy reasons. After the conflict, most of the stations reopened but some of them, including Liège, didn’t and they became known as the stations fantômes, or ghost stations. Liège station eventually reopened in 1968 but only with a limited service and it wasn’t until as late as December 2006 that the station began to operate a full service.

One of the features of Liège métro station is the platform office to be found on each platform. I have visions of them once being occupied by an authoritarian early twentieth-century stationmaster or maybe an equally authoritarian ticket collector. In fact, they date from the twenty-first century renovation of the station.

Of all the features of this station though it is the decorative ceramic panels made up of 6,576 ceramic tiles that dominate. There are eighteen panels altogether, nine on each platform.

On one platform are those designed by Daniel Hicter, each of which has a blue tone:

– Coo, dans la vallée de l’Amblève

– Les premières neiges en Fagnes

– Le barrage de La Gileppe

– L’Eglise romane de Momalle

– Le village de Limbourg

– Le château de Jehay-Bodegnée

– Le circuit automobile de Spa-Francorchamps

– Le château de Chokier-sur-Meuse

– Le Palais des Princes-Evêques de Liège

And on the other platform are those by Marie-Claire Van Vuchelen, each with a brown-ochre tone:

– La vallée du Hoyoux à Modave

– La vallée de la Vesdre à Nessonvaux

– Le Château de Wégimont à Soumagne

– Le Perron de Liège

– L’Hôtel de Ville de Verviers

– Le pont, la collégiale et la citadelle de Huy

– La maison Curtius à Liège

– Le Château de Colonster dans la Vallée de l’Ourthe

– L’Hôtel de Ville de Visé

If you’re travelling on Line 13 of the Paris Métro, it’s well worth getting off at Liège to have a look at these ceramic panels – even if you do now have to peer through the glass panels of the automatic platform doors.

End of the Line – Château de Vincennes

THE ‘END OF THE LINE’ STRAND in my Paris Soundscapes Archive is dedicated to the sounds I capture in and around each terminus station on the Paris Métro system. From time to time I will share the atmosphere of some of these terminus stations and their surroundings on this blog.

In my last ‘End of the Line’ post I explored in and around the Métro station Les Courtilles, the branch of Paris Métro Line 13 terminating in the northwest of Paris. Today, I will share with you my exploration in and around Métro station Château de Vincennes, the easterly terminus of Paris Métro Line 1.

Opened in 1900, Métro Line 1 was the first Paris Métro line to be opened although it was shorter then than it is now. Today, it runs for 16.5 km from La Défense in the west of the city to Château de Vincennes in the east and well over half a million people use it each day making it the busiest line on the Paris Métro system.

In 2007, work began to convert the line from being manually driven to becoming a fully automatic, driverless, operation. The work was completed in 2011 and involved the introduction of new MP 05 rolling stock and the erection of platform edge doors in all stations.

I recorded my arrival at Château de Vincennes station, a ride up a creaky escalator, a walk across the station concourse, up another escalator and out into the street above.

Arrival at Château de Vincennes:

Both the name of the station and a display in the station concourse give us a clue to at least one thing we might find outside.

Vincennes is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the eastern suburbs of Paris. As well as its famous castle, the Château de Vincennes, once home to French Kings, Vincennes is also known for the adjacent 995 hectare (2,459 acres) Bois de Vincennes, the largest public park in Paris, a zoo, the Paris Zoological Park, a botanical garden, the Parc Floral de Paris, and a large military fort once used as a proving ground for French armaments. Vincennes is also home to the Service Historique de la Défense, which holds the archival records of the French Armed Forces.

A short walk from the Métro station I discovered the Cours Marigny, a promenade between the Château de Vincennes and the Hôtel de Ville undergoing a makeover due to be completed in the Spring of 2018.

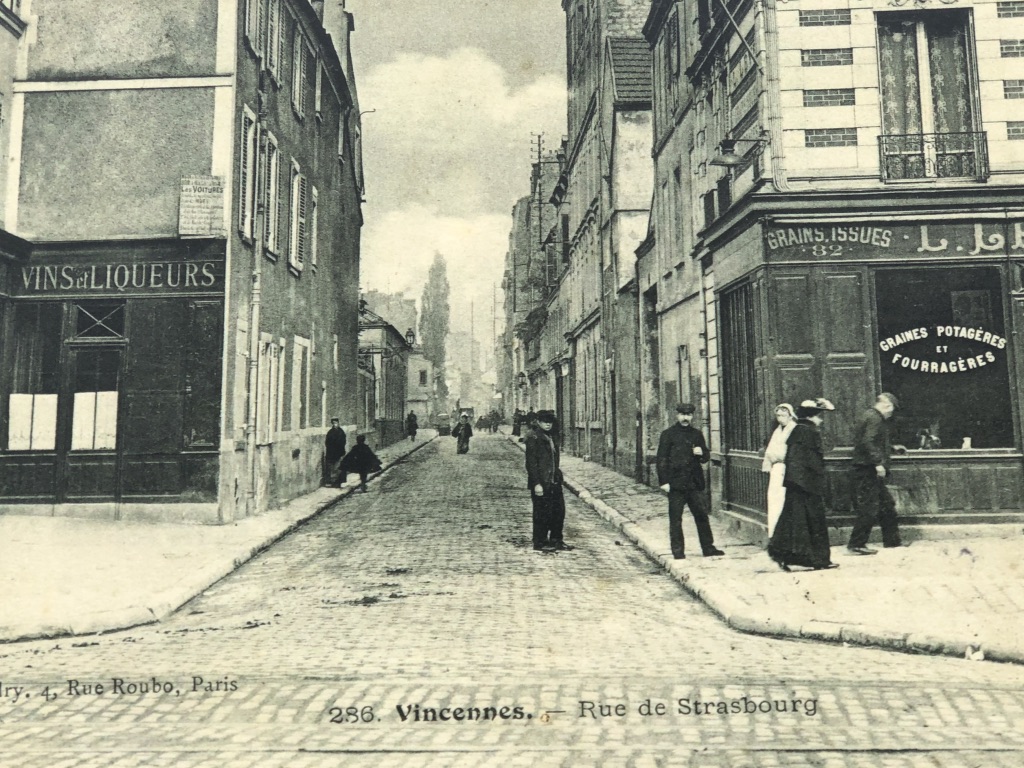

In the town square I found a display of old photographs showing Vincennes as it once was.

But in Vincennes, town and crown sit cheek by jowl so the château is never far away.

The Château de Vincennes is a massive former French royal fortress, which originated as a hunting lodge constructed for Louis VII around 1150 in the forest of Vincennes. In the 13th century, Philip Augustus and Louis IX, King of France from 1226 until his death during the eighth crusade in 1270, erected a more substantial manor.

King Louis IX – Saint Louis, outside the Château de Vincennes

By the 14th century, the Château de Vincennes had expanded and outgrown its original site. With the outbreak of the Hundred Years War, it became as much a fortress as a family home. Philip VI added a donjon, or fortified keep, which at 52 meters high was the tallest medieval fortified structure in Europe at the time. The grand rectangular circuit of walls was completed in about 1410.

The donjon served as a residence for the royal family and its buildings are known to have once held the library and personal study of Charles V. In 1422, seven years after his victory at Agincourt, Henry V of England died in the donjon from dysentery, which he had contracted during the siege of Meaux.

By the 18th century, the Château de Vincennes had ceased to become a practical fortress. Instead it became home to the Vincennes porcelain manufactory, precursor to the Sèvres porcelain factory, and the keep became a prison housing such distinguished guests as the Marquis de Sade, Diderot, and the French revolutionary, the Comte de Mirabeau,

Sounds around the Métro station Château de Vincennes :

To capture the ‘End of the Line’ atmosphere around the Métro station Château de Vincennes I recorded while sitting on a green bench alongside the wall and the moat on the western side of the château, close to one of the Métro entrances and even closer to the donjon and its bell tower. The sounds are the everyday sounds of this leafy part of Vincennes, including the chiming of the donjon bell.

In his book, Nairn’s Paris, a unique guide to Paris published in 1968, the British architectural critic, Ian Nairn, has a particular view about the Château de Vincennes:

“The château must be one of the most bad-tempered collections of buildings in the world, full of the prose of containment without any of the poetry of castellation. The vast medieval curtain-wall is opened out at the south end, towards the Bois, with grumpy classical buildings by Le Vau: on the north side there is the entrance tower, and brooding over the whole cross-grained mixture is the fourteenth-century donjon, which they say is the tallest in Europe; five huge storeys, surrounded by its own curtain-wall. Inside, the tall rooms, each heavily vaulted from a single pillar, give away nothing more than the facts of incarceration, if anything reinforced by the Gothic ribs and corbels that are familiar from less gloomy places. It is no illusion: Vincennes has a grim record and the tiny ill-light cells are still there to prove it.

[…]

One final view, the only soft thing at Vincennes: the eastern side of the moat, choked with big trees, Nature at last getting its own back on man. But the town that has grown up opposite this wicked uncle is as different as could be – a kind of French Aldershot. Vincennes has many barracks, some of them still inside the walls, and France has compulsory military service. Across the road from the château is a bus terminus, the end of a Métro, a line-up of cheerful cafés, and a considerable variety of, cheerful, cheap, not very good meals.”

Nairn’s Paris by Ian Nairn – Penguin Books (1968)

Just for clarification: For those not familiar with it, Aldershot, to which Ian Nairn refers, is a garrison town in the south of England, and France no longer has compulsory military service. The bus terminus, the end of the Métro and the line-up of cheerful cafés are still there and, although not as cheap as they were, some of the meals at least have improved!

End of the Line – Les Courtilles

AS PART OF THE Greater Paris Project, the plan to create a sustainable and creative metropolis by absorbing the suburbs and redeveloping the city centre, RATP, the Paris mass transit authority, is gradually extending the Métro lines further out into the Parisian suburbs.

This development has prompted me to create a new strand in my Paris Soundscapes Archive, which I’ve called the ‘End of the Line’. The idea is that I will visit the end of each Métro line and collect sounds not only from within the last station on each line but also from the surrounding area outside each station.

Since most Paris Métro lines begin and end at the periphery of the city this will not only be a fascinating way to discover new places but also new sounds. In my experience, the sounds at the periphery of the city often differ markedly from those at the centre so my ‘End of the Line’ strand seems a good way to explore more of these peripheral sounds.

From time to time I will share some of these ‘End of the Line’ explorations on this blog beginning with: ‘End of the Line – Les Courtilles’

The Métro station Les Courtilles, or to give it it’s proper name, Asnières – Gennevilliers – Les Courtilles, is the terminus of the north-western branch of Métro Line 13, the longest line on the Paris Métro network. Situated under the Avenue de la Redoute on the border of the communes of Asnières-sur-Seine and Gennevilliers, the station was opened in 2008 upon completion of the extension of Line 13 from the previous terminus, Gabriel Péri.

In November 2012, Tramway T1 was extended to terminate at Les Courtilles. Between the Métro station and the Tramway, an impromptu African market appears each day together with its characteristic sounds.

As I said, the Métro station Les Courtilles is on the border of the communes of Asnières-sur-Seine and Gennevilliers, with Gennevilliers being to the north-east of the station. Looking out over Gennevilliers from the Métro station, the view is dominated by the tourist-free zone, Le Luth, a huge social housing complex.

Shortly after I arrived at Les Courtilles so did the rain so, although Le Luth is well within walking distance from the station, I took the tram and travelled one stop to the heart of the complex.

Designed by the architects Auzolle and Zavaroni and completed in 1978, Le Luth is typical of many major residential projects built between the 1950s and the 1970s.

An aerial view of Le Luth via Wikipedia

Le Luth was built both to replace existing sub-standard housing and to provide accommodation for an expanding population and when it was completed it was considered a success.

But with the deindustrialisation of the 1980s and 1990s, companies in the area like Chausson, Carbone Lorraine and General Motors began to shed workers and the area began to decline.

“General Motors France se prépare à supprimer 280 postes de travail d’ici à juillet en raison de l’arrêt de la fabrication d’un système de freinage dans son unité de Gennevilliers.

GM France emploie environ 2.000 personnes à Gennevilliers (sur 5.200 en France) réparties dans trois unités spécialisées dans les freins, les systèmes électriques et les pots catalytiques.

LES ECHOS | LE 05/03/1993

Since 2006, Gennevilliers and Le Luth have been undergoing redevelopment. Efforts have been made to attract new economic activity and public spaces are being re-imagined. Roads have been cut through the undulating housing blocks, old buildings are being renovated or in some cases replaced with smaller housing units, and the extensions to Métro Line 13 and Tram Line T1 are part of this process.

Sounds of Métro station Les Courtilles, the tramway and Le Luth:

The ‘End of the Line’ strand in my Paris Soundscapes Archive is designed to capture the atmosphere in and around the terminus stations on the Paris Métro.

I collected over three hours of sound in and around Les Courtilles Métro station and Le Luth housing complex all of which has been consigned to my archive. For this post though I have distilled those sounds down to a fifteen-minute sonic snapshot, which I hope you find still gives a sense of the atmosphere of these places on a wet Tuesday afternoon.

This sound piece begins with my arrival at Les Courtilles Métro station and the ride up the escalator out onto the street. Then come the African voices in the market outside the station and on the tram ride to Le Luth and finally some sounds I discovered around L’espace Aimé Césaire, the cultural and social centre at the heart of Le Luth.

And what about the name ‘Le Luth’, where does that come from?

One explanation might be that the name derives from the Celtic root, luto- or luteuo-, which means ‘marsh’ or ‘swamp’. After all, Julius Caesar named the predecessor of present-day Paris ‘Lutetia’.

A more simple explanation though might be that, when viewed from the air, the housing complex has a shape similar to the musical instrument, the lute: ‘Luth’ is the French word for ‘lute’.

For me, the most interesting thing about listening to and studying urban soundscapes is not simply listening to the sounds themselves, fascinating as they often are, but rather it is going to new places to find new sounds and then discovering and understanding the historical, social, cultural and political context that surrounds the sounds.

Exploring the ‘End of the Line’ at Asnières – Gennevilliers – Les Courtilles has taken me to a place that I would probably never have visited had I not been hunting for new sounds for my archive. And although I haven’t written about it in great depth here, I am richer for having explored the context in which those sounds occur.

In and Around Métro Lamarck-Caulaincourt

NAMED AFTER THE FRENCH comedian, humorist and member of the French Resistance, rue Pierre Dac is just 23 metres long making it one of the shortest streets in Paris. Originally forming the upper part of rue de la Fontaine-du-But linking rue Lamarck and rue Caulaincourt in the 18th arrondissement, the street’s name was changed in 1995 in honour of Pierre Dac.

The distinctive red sign in rue Pierre Dac points us towards the Métro station Lamarck-Caulaincourt and tells us that this station once formed part of the three Paris Métro lines owned by the Nord-Sud Company, or to give it its proper name, la Société du chemin de fer électrique souterrain Nord-Sud de Paris. In 1931, the Nord-Sud Company was taken over by its competitor, la Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris, which in turn was nationalised in 1948.

The Métro station Lamarck-Caulaincourt is perhaps best known for its distinctive entrance nestling between the two staircases that form most of rue Pierre Dac.

Lamarck-Caulaincourt station was opened on 31st October 1912 and today it forms part of the Paris Métro Line 12 linking the stations Front Populaire in the north to Issy-les-Moulineaux in the south. The station platforms were renovated in 2000 – 2001 and further work was carried out in 2006.

Lamarck-Caulaincourt platform before renovation

Lamarck-Caulaincourt platform today

Since Lamarck-Caulaincourt station was constructed under the butte Montmartre, the large hill that forms the village of Montmartre, it’s not surprising that the station platforms are some 25 metres below the station entrance. For those who arrive at the station by train and find the 25-metre climb out of the station a challenge, RATP have thoughtfully provided a lift to make life easier.

Sounds around Lamarck-Caulaincourt station platforms and an exit by lift:

I recorded the sounds inside the station to add to my extensive archive of sounds of the Paris Métro network but I also recorded sounds from the staircases in rue Pierre Dac outside the station, which I found to be equally fascinating.

I sat on one of the staircases and simply observed life passing by just as the photographer did in the 1925 photograph below.

L’entrée de la station de métro Lamarck-Caulaincourt entre les escaliers de la rue de la Fontaine-du-But, vers 1925. Photo collection Jean-Pierre Rigouard.

Sounds from the staircase in rue Pierre Dac:

Entrance to the Métro station Lamarck-Caulaincourt between the staircases in rue Pierre Dac (formerly la rue de la Fontaine-du-But), August 2017

Sitting on a staircase in the street observing the world passing by might not be everyone’s idea of a good day out, but at least I wasn’t the only one!

Observing through active listening is what I do and whether it’s the sounds of a Métro station platform or the sounds of a staircase in the street I’m always captivated by the stories sounds have to tell to the attentive listener.

Although we can see from the photograph what this place looked like in 1925, I can’t help wondering what it sounded like then and what stories those sounds would have told us.

Gare d’Austerlitz and its Changing Sounds

SOME TIME AGO I reported that the Gare du Nord, one of the six main line railway stations in Paris and the busiest railway station in Europe, is undergoing a transformation. But it’s not only the Gare du Nord that is being transformed. On the left bank of the Seine, in the southeastern part of the city, another Parisian main line station is having a major facelift.

Since 2012, work has been underway at Gare de Paris Austerlitz, usually called Gare d’Austerlitz, to construct four new platforms, refurbish the existing tracks and rebuild the station interior. The renovation work will be completed by 2020 thus doubling the capacity of the station to accommodate some of the current TGV Sud-Est and TGV Atlantique services which will be transferred from Gare de Lyon and Gare Montparnasse, both of which are at maximum capacity.

The redevelopment of Gare d’Austerlitz is not confined to the station itself. It will also include developing some 100,000 M² of land between the station and the neighbouring Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière to include housing, offices, public facilities and businesses.

Built in 1840 to serve first the Paris-Corbeil then the Paris-Orleans line, the station, known originally as Gare d’Orléans, underwent its first makeover between 1862 and 1867 to a design by the French by architect Pierre-Louis Renaud, much of which is what we see today.

The name, Gare d’Austerlitz was adopted to commemorate Napoléon’s victory at the Battle of Austerlitz in December 1805.

Métro Line 5 arrived at Gare d’Austerlitz in 1906, the station survived the great flood of 1910 and in 1926 it became the first Parisian railway station to stop handling steam trains when electrification arrived.

Although the smallest of the Parisian main line stations, until the late 1980s Gare d’Austerlitz was one of the busiest with services not only to Orléans but also to Bordeaux and Toulouse. However, with the introduction of the TGV Atlantique using Gare Montparnasse, Gare d’Austerlitz lost most of its long-distance southwestern services and the station became a shadow of its former self. About 30 million passengers a year currently use Gare d’Austerlitz, about half as many as use Gare Montparnasse and a third as many as use the Gare du Nord.

The 21st century makeover of Gare d’Austerlitz will see the station upgraded to handle TGV trains, some of its former southwestern services restored and its capacity doubled.

Capturing the sounds of Paris is what I do and capturing changing soundscapes of the city has a special fascination for me. Any renovation of public spaces not only changes the visual aspect of the place but also its soundscape and so I am anxious to follow how the soundscape of the Gare d’Austerlitz will change as the current development unfolds.

This is what the station sounds like today:

Gare d’Austerlitz and its sounds:

It will be interesting to compare these sounds with sounds recorded from the same place in 2020 when the work is completed.

Of course, we don’t have to wait until 2020 to find a changing soundscape around Gare d’Austerlitz. We only have to go up from the main station platforms to the Métro station Gare d’Austerlitz to discover how soundscapes change over time.

These are sounds I recorded on the Métro station platform in 2011 when the old, bone shaking, MF67 trains were running.

Métro Line 5 – Gare d’Austerlitz in 2011

And these are sounds I recorded this year from exactly the same place. The difference is that the old rolling stock has been replaced with the newer, more energy efficient, smoother running, much more comfortable, air-conditioned, MF01 trains.

Métro Line 5 – Gare d’Austerlitz in 2017

The old MF67 trains no longer ply Line 5 of the Paris Métro and their iconic sounds have gone forever. I believe that the everyday sounds that surround us are as much a part of our heritage as the magnificent buildings that grace this city and, although change is inevitable and often for the better, the sounds we lose in the process deserve to be preserved.

Just as the sounds on Métro Line 5 have changed so will the sounds in and around Gare d’Austerlitz as its renovation unfolds. And I will be there to capture the changing soundscape for posterity.

Métro Station ‘Assemblée Nationale’ and its Sounds

RETURNING FROM A recording assignment in the 7th arrondissement the other day, I called into the nearest Métro station, Assemblée Nationale, to catch a train home. Faced with a choice of two entrances to the station I couldn’t resist using the elegant Hector Guimard entourage entrance with its classic red METROPOLITAIN sign, distinctive of the former Nord-Sud line, instead of the rather plain entrance across the street.

The station was opened on 5th November 1910 as part of the original section of the Nord-Sud Company’s line between Porte de Versailles and Notre-Dame-de-Lorette. The Nord-Sud Company (Société du Chemin de Fer Électrique Nord-Sud de Paris) was established in 1904 and built two underground lines, now line 12 and part of line 13. The company was taken over by the Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris (CMP) in 1930 and incorporated into the Paris Métro.

The station was originally called Chambre des Députés, the former name of the French National Assembly, a name the station held until 1989 when it became Assemblée Nationale.

Both the original and the current name of the station of course derive from the Palais Bourbon, the seat of the French National Assembly, the lower legislative chamber of the French parliament, which stands close by.

The Palais Bourbon – The Assemblée Nationale

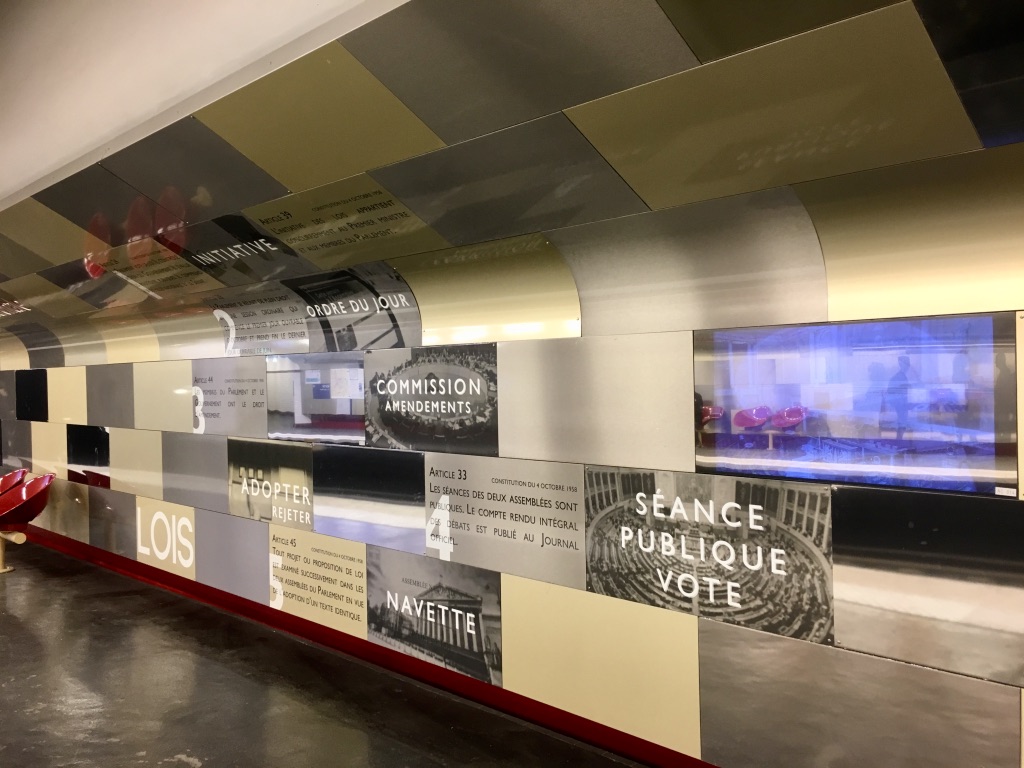

The identifying feature of Métro station Assemblée Nationale is that there are no advertisements anywhere in the station. Instead, the walls sport ninety-metre long murals featuring various aspects of the work of the National Assembly. The murals are changed with each renewal of the legislature.

Both the Palais Bourbon and the Hector Guimard métro station entrance are located in Faubourg Saint-Germain, an aristocratic neighbourhood bristling with government ministries and foreign diplomatic embassies and it was from here that I descended into the station. Once on the platform, I paused to examine the murals and listen to the sounds in the station before boarding a train to take me home.

This is what I saw and heard:

The Métro Station Assembléé Nationale and its Sounds:

Paris Flood 2016

SEARCH WIKIPEDIA FOR ‘Paris Flood’ and this is what you will most likely find:

“In late January 1910, following months of high rainfall, the Seine River flooded Paris when water pushed upwards from overflowing sewers and subway tunnels, and seeped into basements through fully saturated soil. The waters did not overflow the river’s banks within the city, but flooded Paris through tunnels, sewers, and drains. In neighbouring towns both east and west of the capital, the river rose above its banks and flooded the surrounding terrain directly.”

Fast forward a hundred years or so to the beginning of June 2016 and the question on most Parisians’ minds was: “Will history repeat itself?”

Place Louis Aragon; 4th Arrondissement; June 2016

After a prolonged period of rain last month, the waters of the Seine, Loire and Yonne rivers began to rise alarmingly. In the départements of Loiret and Seine-et-Marne the rivers broke their banks causing what French President, François Holland, described as a “real catastrophe”.

In Paris, the Seine didn’t break its banks but, rising to some 6.3 metres above normal on the night of Friday 3rd June, it came dangerously close.

The sight of dirty brown water and debris floating through the centre of the city was surreal.

Although the Seine didn’t break its banks in the city, the quais on either side of the river were completely flooded giving a clue at least as to what those in the worst affected départements were experiencing.

A five-minute walk from my home, the Seine had completely covered an island jutting out into the river. The Parisian green benches, the skateboard park and the honey farm with its beehives were completely submerged.

A nearby tennis court was looking the worse for wear.

And the péniches (houseboats) had been cast adrift.

On Saturday 4th June the news was that although the water hadn’t fallen, at least it had stopped rising and so, with the photograph of the policemen shown at the beginning of this post standing in front of the Viaduc d’Austerlitz in 1910 in mind, I went to the same place to see what I could find.

Completed in 1904, the Viaduc d’Austerlitz is a 140-metre single-span bridge built to carry the trains of Métro Line 5 over the Seine from the Quai de la Rapée to the Gare d’Austerlitz and back again. With an 8.5 metre wide deck suspended 11 metres above the river the bridge was designed to make it easily navigable for river traffic.

During the recent crisis all river traffic was suspended because the exceptionally high water level made the bridges over the Seine impassable.

Underneath the bridge the quay is usually open to pedestrians and vehicular traffic but on Saturday it was flooded despite a hastily erected barrier being in place.

What does a flood sound like? Would there be a sound-rich raging torrent of water crashing it’s way through the city?

I thought about this as I watched the water rise over several days and I discovered that it didn’t happen like that. There was no raging torrent but instead, an almost silent, inexorable flow of water calmly engulfing everything in its path.

On Saturday, with the floodwater passing by me and the trains of Metro Line 5 passing overhead, I recorded the sounds around the Viaduc d’Austerlitz. It wasn’t the sounds of the vast quantity of ugly brown water flowing along the river that caught my attention but rather the more delicate sounds on the flooded quais.

The Paris flood 2016 around the Viaduc d’Austerlitz:

With a repetition of the catastrophic Paris flood of 1910 avoided, the floodwater is beginning to recede. Water pumps have been drafted in, the clean-up operation has begun and the cost is being estimated somewhere between €600 million and €2 billion.

It’s easy to lament the situation in Paris over the past few days: the flooded quayside bars and restaurants, the péniches cast adrift, the closure of the Louvre and the Musée d’Orsay to move their collections from ground level to higher floors, the occasional power outage and the closure of some Métro stations and part of RER Line ‘C’.

But let’s not forget the 4 dead, at least 24 injured and thousands of residents in towns such as Nemours and Montargis who saw their homes submerged and shop owners left counting the cost as the town centres were inundated by the floods.

The Métro Station ‘Cité’ and its Sounds

WITH ITS UBIQUITOUS Hector Guimard ‘entourage’ entrance, the Métro station Cité is the only Métro station on the Île de la Cité, one of the two islands on the Seine within the historical boundaries of the city of Paris.

The entourage entrance was the most common of Guimard’s Métro entrances. Built in the Art Nouveau style the entrance has waist high cast iron railings around three sides with symmetrical raised orange lamps designed in the form of plant stems, with each lamp enclosed by a leaf resembling a brin de muguet, a sprig of lily of the valley. Between the lamps is the classic Metropolitain sign.

Of the 154 entourage Métro entrances built, some 84 still survive on the Paris streets.

With the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris on one side and the medieval gothic chapel, Sainte-Chapelle, the Conciergerie (a former prison) and the Palais de Justice (all formerly part of the Palais de la Cité, a Royal Palace from the 10th to the 14th century) on the other, Cité Métro station lies at the historical centre of Paris.

The station is on Line 4 of the Paris Métro system, the line that travels 12.1 km across the heart of the city connecting Porte de Clignancourt in the north and, since 2013, Mairie de Montrouge in the south. Until the extension to Mairie de Montrouge was opened, the southern terminus of Line 4 was the original terminus, Porte d’Orléans.

Métro Line 4 was the first line to connect the Right and Left Banks of the Seine via an underwater tunnel built between 1905 and 1907. At the time, this was some of the most spectacular work carried out on the Paris Métro system.

Crossing the Seine was achieved using caissons, assembled on the shore and then sunk gradually into the river bed. The metal structures of the two stations, Cité on the Right Bank and Saint-Michel on the Left Bank, were also assembled on the surface and then sunk into the ground to their final location.

Station La Cité. Fonçage du caisson elliptique à la fin de la station. Vue intérieure. Vers le boulevard du Palais. Paris (IVème arr.). Photographie de Charles Maindron (1861-1940), 18 janvier 1907. Paris, bibliothèque de l’Hôtel de Ville. © BHdV / Roger-Viollet

Image courtesy of Paris en Images

The Seine crossing was commissioned on 9th January 1910 … only to be closed a few days later, a victim of the great Paris flood of 1910.

Cité Métro station was opened on 10th December 1910.

Unusually for the Paris Métro system, the station only has one entrance, at 2 Place Louis Lépine and, unlike other stations on Line 4, the platforms are 110 m in length, longer than the 90-105m platforms at other stations.

Because of the station’s depth, passengers must walk down to a mezzanine level, which contains the ticket machines, and then down another three flights of stairs before reaching platform level. This is fine on the way down but, as I know all too well, it can be a challenge on the way up!

The walls of the station at the entrance at the top and along the platforms at the bottom are lined with conventional white Métro tiles but the decoration of the space in between is curious.

Here, the walls are lined with large metal plates with oversized rivets. I have no idea when these were installed or why, but they give the impression of walking through a huge metal tank.

The station platforms are lined with overhead lamps reflecting the style of the original station lamps.

Until recently, Métro Line 4 had the distinction of using the oldest trains on the Paris Métro network, the MP 59.

Paris Métro train Type MP 59 : Image via Wikipedia

After serving for almost fifty years, these trains were withdrawn from service during 2011 and 2012 and replaced with the MP 89 CC trains from Line 1 when that line was automated.

An MP 89 CC train at Cité station, formerly used on Métro Line 1

Sounds inside Cité Metro Station:

I began recording these sounds at the Cité Métro entrance in Place Louis Lépine, beside the flower market. I went down the steps to the mezzanine level, passed through the ticket barrier, and then descended two more flights of steps. From here, it’s possible to see and hear the trains passing below. I walked along the narrow passageway beside the riveted metal plates and down some more steps to the platform.

Watching and listening to the MP 89 trains entering and leaving the station was quite nostalgic for me since I know these trains so well. When they operated on Line 1, the nearest line to my home, I rode on these trains almost every day for the best part of thirteen years.

I was pleased to see my old friends again at Cité station busy carrying passengers on the second busiest Métro Line in Paris.

Having savoured the atmosphere of the station, all that remained was for me to bid my friends adieu and gird my loins for the climb out of the station back onto the street.

Music in the Métro

IT’S BEEN A WHILE since I last featured any street music on this blog but I now have the opportunity to put that right.

Changing trains at the Métro station Charles de Gaulle Étoile the other day I came upon a street musician who is often to be found playing his xylophone on the platform of Métro Line 6, the line that follows a semi-circular route around the southern half of the city from Étoile to Nation.

Getting a seat on a train on Line 6 at Étoile can sometimes be a challenge. A large crowd often assembles on the platform and I usually find myself forsaking the pleasure of listening to the music in favour of elbowing my way through the crowd in the hope of securing a seat on the arriving train. Which is a shame really because most of the musicians playing in the Métro stations are very good.

It’s not generally known, but musicians who play in the Métro – at least those who play there legally – have actually been selected to play there following a formal audition process.

The auditions were introduced because the Métro was becoming infested with itinerant so-called musicians who could barely scrape out a note from their battered violins or accordions.

Now, some 2,000 musicians attend the auditions and the artistic director of the Musiciens du Métro programme and representatives of RATP, the Paris mass-transit authority, judge their performances. Only 300 of them will be awarded the coveted badge that lets them play legally in the Métro and so, with a potential audience of some four million passengers a day, that’s a gig worth having.

When I was changing trains at Étoile the other day I had time on my side so I stopped to listen to the xylophone player, one of the successful badge holders, playing his music. And what a delight it was!

Music on the Métro: