The Changing Soundscape of the Gare du Nord

THE GARE DU NORD railway station in Paris is on the cusp of great change. Over the next few years the physical architecture of this station will be transformed and consequently, so will its sonic architecture.

For many years I have been recording and archiving the sounds of the Gare du Nord. My particular interest lies in investigating how sounds can define, or help to define, a place and how the soundscape of a particular place changes over time. The Gare du Nord is a valuable case study in both these areas.

The first Gare du Nord station was built in 1846 but an increase in traffic meant that a new, bigger station was soon required.

The original 1846 chemin de fer du nord station

Rebuilding took place under the direction of the German-born French architect Jacques Ignace Hittorff with the new station combining the advanced structural use of new materials, notably cast iron, with conservative Beaux-Arts classicism. Hittorff’s Gare du Nord was completed in 1864.

La “Gare de la Compagnie du chemin de fer du Nord” photographiée vers 1864 par Charles-Henri Plaut

Significant changes to the station were made in 1981 to accommodate RER Line B and then in 1993 to accommodate the TGV and the Eurostar. The last major change was 2001 with a major expansion of the departures hall.

Gare du Nord TGV Departure Hall in 2017

And now the Gare du Nord is about to undergo further change.

Subject to negotiations due to be concluded by the end of this year, SNCF Gares & Connections and the global real estate company Ceetrus will set up a joint venture to carry out a transformation of the Gare du Nord. Ceetrus, in association with architect Denis Valode (Valode and Pistre architects), will lead a transformation as big as that led by the Hittorff in 1864. The transformation is due to be completed in time for the Paris Olympic Games in 2024.

Artist’s impression of the transformed Gare du Nord

The transformation will see the station triple in size from 36,000m2 to 110,000 m2. With 700,000 passengers using the station each day, excluding those who use the associated Métro station, the Gare du Nord is already the busiest railway station in Europe. Following the transformation the daily passenger numbers are expected to increase to 800,000 in 2024 and 900,000 in 2030.

The transformation will include a new departure terminal in which the flow of arrivals and departures from the station will be distinct thus improving fluidity and comfort for travellers. A new station facade is proposed on rue du faubourg Saint-Denis with direct access to the departure terminal.

The Eurostar terminal will be expanded to meet the challenge of strengthened customs controls linked to Brexit.

Accessibility will be enhanced with more elevators and escalators. The new station will have 55 lifts and 105 escalators. Station security will be enhanced with more CCTV being installed.

Access to the three metro lines will be improved. The bus station with its 12 bus lines and 7 Noctilian services will be connected directly with the departure terminal, and 1,200 bicycle parking spaces will be available with direct access from the square in front of the station.

Traffic circulation around the station will be redesigned to take account of the redesigned access to the station and also the expected development of new electric mobility solutions.

The transformed station will also include a 2,000 m2 ‘European Academy of Culture’, a concept devised by the writer Olivier Guez, including a 1,600 m2 space to host events and concerts.

There will be 5,500 m2 of co-working space, a nursery, new restaurants and a one-kilometre running track on the station roof.

Artist’s impression of the transformed Gare du Nord

The transformation of the Gare du Nord will clearly change the visual landscape of the station but it will also change its sonic landscape. There are six main line railway stations in Paris, five of which sound very similar. The exception is the current Gare du Nord, which has a very distinctive soundscape. The size of the main departures terminal together with Hittorff’s 19th century iron and glass construction and the cacophony of waiting passengers squeezed between the parked trains and the street outside gives the Gare du Nord a very particular sonic ambience.

This is what the Gare du Nord sounded like in 2011.

Gare du Nord 2011:

Gare du Nord Departures Hall 2011

Although the major transformation project is not due to start until next year, some improvements to the Gare du Nord are already underway. When I went there last week I found men laying a new stone floor in the main departures hall, which gives us a clue as to how the soundscape of the station will change as the major construction work progresses. The sounds of the gasping trains will have to compete with the cacophony of building work for some considerable time to come.

Gare du Nord 2018:

Having recorded the soundscape of the current Gare du Nord many times I shall continue to record and archive the sounds as the station’s transformation takes place. I shall be fascinated to discover the sounds of the new, ultra-modern Gare du Nord when all the work is completed. I will though still go back to my archive from time to time and listen to the sounds of the ‘old’ Gare du Nord; sounds that have been so familiar to me for almost the last twenty years and sounds that are about to disappear.

Artist’s impression of the transformed Gare du Nord

La Fête Nationale 2018

YESTERDAY, 14th JULY, WAS a day of national celebration in France. Le Quatorze Juillet, also known as La Fête Nationale, but never Bastille Day as it’s often referred to in English-speaking countries, is the French national day commemorating the 1790 Fête de la Federation held on the first anniversary of the storming of the Bastille on 14th Jul 1789.

Although the day is marked across France, the centerpiece event takes place in Paris with the défilé, the parade of military and civilian services, marching down the Champs Élysée to be reviewed by the Président de la République.

Each year on 14th July a huge crowd lines the Champs Élysées to watch the parade, although how many of them actually see anything is questionable. I though always head to the west of Paris, conveniently close to home, to enjoy a close-up view of the defile aérien, the fly past of aircraft and helicopters of the military and civilian services heading for the Champs Élysées. Being a lifelong enthusiast of both sound recording and aviation, recording a flotilla of aircraft and helicopters flying overhead in close formation at 1,000 feet seems to me to be a perfect way to spend a morning.

A note to the loyal readers who come to this blog to learn more about the social and cultural history of Paris and to enjoy the everyday sounds of the city: Although the rest of this post may seem more suited to aviation geeks like me, please stick with it because, if nothing else, I’m sure you will enjoy the sounds!

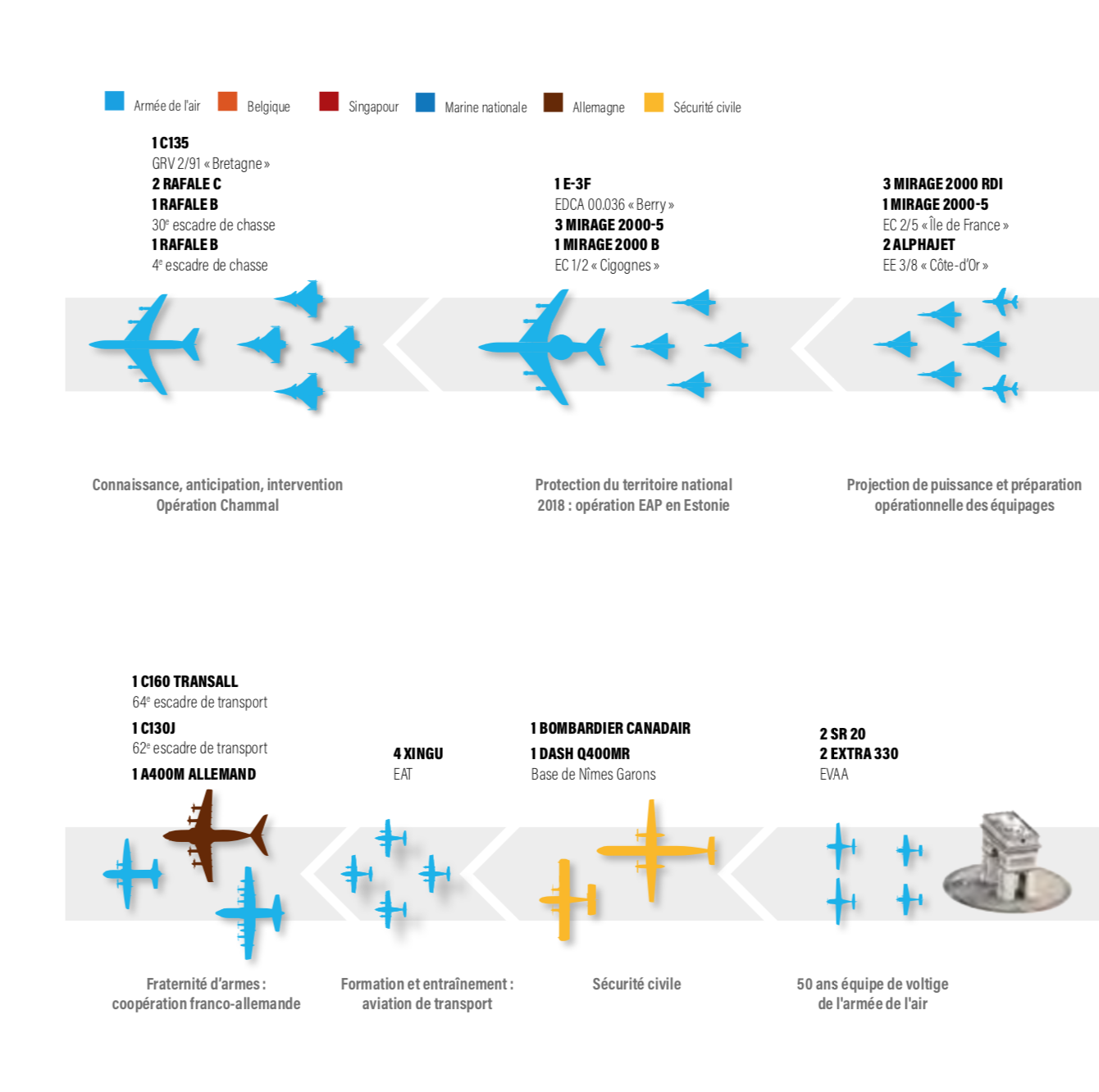

This year, 64 fixed wing aircraft took part in the defile aérien: 53 from l’armée de l’air (the French Air Force), 6 from la marine nationale (the French Navy), 2 from la sécurité civile and 3 from other countries comprising an M346 advanced training aircraft from the Republic of Singapore, an Alpha Jet from the Belgian Air Force and an A400M military transport aircraft from the German Air Force.

As always, the défilé aérien opened with nine Alpha Jets of the Patrouille de France, the French aerobatic display team, flying their ‘Big Nine’ formation. But this year there was a twist, an unintentional twist, or as France Info put it: “La Patrouille de France s’est emmêlée les pinceaux dans les couleurs du drapeau.” In other words, the Patrouille de France got in a tangle with the colours of the French flag.

Take a look at the aircraft on the far left of the picture. When a pilot flying in close formation makes a mistake it usually ends badly, but when a pilot in a prestigious aerobatic display team presses the wrong button and emits red instead of blue smoke then that is undoubtedly a bad career move.

Here is a schematic of the aircraft fly past from which you can see the variety of aircraft involved this year.

The logistics involved in parading all these aircraft one after the other are complex, not least because the maximum speed of some of the aircraft is slower than the slowest speed of others.

Here are some facts:

From the first aircraft to the last, the fly past stretches for 50 kilometres with 6 kilometres between each block of aircraft. The space between the aircraft flying in close formation is between 5 and 10 metres.

All the aircraft fly past at 1,000 feet, or 305 metres.

The fighter aircraft fly past at 300 knots, around 550 km/h; the navy fighters at 280 knots, around 520 km/h; the navy patrol aircraft at 200 knots, around 370 km/h and the transport aircraft at 180 knots around 330 km/h.

And this is what they sounded like as they passed me today:

Aircraft Fly Past 2018:

I record the sounds of the défilé aérien every year but this year I was able to find a spot to record from that was devoid of people and almost out of earshot of traffic – a rare find indeed.

Some forty-five minutes after the parade of fixed wing aircraft it was time for the rotary wing flotilla; the helicopters.

Here is a schematic showing the helicopters on display today.

This year, there were 30 helicopters, including 18 light aviation helicopters from the army; five helicopters from the air force; two from the navy; three from the gendarmerie and two from the sécurité civile.

From the first helicopter to the last, the fly past stretched for 8 kilometres with 1 kilometre between the two main aircraft blocks. They flew at a height of 400 feet, 120 metres, at a speed of 90 knots or 170 km/h.

And this is what they sounded like as they passed overhead:

Helicopter Fly Past 2018:

While recording the sounds of the défilé aérien I was able to use my smart phone to take some pictures. Unfortunately, my competence at multitasking didn’t stretch to capturing pictures of every passing aircraft so, for those of you who would like to know more about at least some of the aircraft taking part in this year’s défilé aérien here are some of the pictures I captured.

A C135 air refueling tanker from Flight Supply Group 2/91 “Brittany”, followed by a Mirage 2000N from Fighter Squadron (EC) 2/4 “La Fayette”, and three Rafale from EC 1/4 “Gascogne”.

An Airbus A330 MRTT (Multi Role Tanker Transport), a new multi-role aircraft providing personnel and freight transport, air refueling and intelligence gathering. It is followed by four Mirage 2000D from N° 3 Fighter Wing.

A C135 refueling aircraft from Flight Replenishment Group 2/91 “Brittany” followed by four Rafale (three Rafale C two-seater and one single-seater Rafale B) from the 30th Fighter Wing.

An Awacs E-3F from the Airborne Warning and Control Squadron 00/036 “Berry” followed by four Mirage 2000-5s from EC 1/2 “Cigognes”.

Four Mirage 2000 from the EC 2/5 “Ile-de-France” and two Alpha Jets from the 3/8 “Côte d’Or” training squadron, the only French squadron simulating enemy action to train pilots and confronting them with all types of threats.

Two Alpha Jets from l’École d’aviation de chasse (EAC) at̀ Tours and three Alpha Jets from l’École de transition opérationnelle (ETO) at Cazaux, including one Belgian Alpha Jet, and one Singaporean M346 from the 150th Squadron stationed at Cazaux Air Base. For 20 years, a detachment of the Singapore Air Force has been stationed there to train its fighter pilots.

An Airbus A340 from the 3/60 “Esterel” Transport Squadron.

An A400M Atlas from 61 Wing and two Casa CN 235 from 1/62 “Vercors” and 3/62 “Ventoux” Transport Squadrons.

A Canadair CL415 and a Dash Q400 MR from la sécurité civile used in fighting forest fires. These aircraft have been deployed in the firefighting role in France, Europe and in the rest of the world.

Two Airbus lightweight, multipurpose Fennec helicopters from the helicopter squadron 3/67 “Parisis” and one from 5/67 “Alpilles”.

One EC145 and two EC135 helicopters from the gendarmerie nationale.

An HAP Tiger, followed by a Cougar, and a Gazelle from the 4th Special Forces Helicopter Regiment.

End of the Line: La Défense – Grande Arche: Part 1

THE ‘END OF THE LINE’ STRAND in my Paris Soundscapes Archive is dedicated to the sounds I capture in and around each terminus station on the Paris Métro system. From time to time I share the atmosphere of some of these terminus stations and their surroundings on this blog.

In previous ‘End of the Line’ posts I’ve explored the sounds in and around the Métro station Les Courtilles, the branch of Paris Métro Line 13 terminating in the northwest of Paris, and the sounds in and around Métro station Château de Vincennes, the easterly terminus of Paris Métro Line 1. Now I’m going to explore the sounds in and around the Métro station La Défense – Grande Arche, the westerly terminus of Métro Line 1.

However, to make this ‘End of the Line’ segment more manageable I will divide it into two parts. Today’s post, Part 1, explores inside La Défense – Grande Arche station and the next post, Part 2, will explore the sounds around the station in what is said to be Europe’s largest purpose-built business district containing most of the Paris urban area’s tallest high-rise buildings.

La Défense looking to the West

Because it serves the largest business district in the Paris region, La Défense – Grande Arche is a multi-functional transport hub. Not only is it home to the western terminus of Métro Line 1, it also houses a Transilien suburban train station, an RER station, a tram station and a bus station, all designed principally to handle the huge number of commuters who travel to and from work in La Défense each day.

La Défense – Grande Arche: The main concourse

The business district of La Défense is so big that it actually has two Métro stations. Esplanade de la Défense is the first of these so it was approaching here on my way to La Défense – Grande Arche that I began my sonic exploration.

Exploring La Défense – Grande Arche station in sound:

Opened on 19th July 1900, Métro Line 1 is the oldest line on the Paris Métro network. Built by the one-armed railway engineer Fulgence Bienvenüe, to connect various sites of the 1900 Exposition Universelle, the original line comprised eighteen stations between Porte Maillot and Porte de Vincennes. In 1934, the line was extended to the east from Porte de Vincennes to Chateau de Vincennes and in 1937 it was extended to the west from Porte Maillot to Pont de Neuilly. In 1992, Line 1 was extended again to the west from Pont de Neuilly to La Défense. In 2007, work began to automate Line 1 and on 15th December 2012 a fully automatic service was introduced. Today the 16.5 km Métro Line 1 is the most utilised line on the Paris Métro network handling over 600,000 passengers per day.

Arriving at the La Défense – Grande Arche terminus, I alighted and made my way up to the cavernous station concourse. This used to be a dingy, inhospitable place but a recent coat of paint has brightened it up a bit and now, the usual suspects cater for the commuters.

From the main concourse I headed off to explore the tram station, home to Tram Line T2.

Tram Line T2, linking the south-west suburbs of Paris with La Défense, began operating in 1997. The tramway was built on the former train line thus making it independent from the road. An extension In 2009 added five more stations towards the south, extending to Port de Versailles and in November 2012, another 4.2 km northern extension beyond La Défense to Bezons added a further seven stations.

The extensions to Tram Line 2 are part of a larger scheme in the Île-de-France aiming to increase connectivity of the suburbs by creating up to 70km of bus and tramways around Paris.

The Transilien suburban trains operate from platforms adjacent to but separated from the tram platforms.

While the public address announcements in the main station concourse are almost unintelligible, those in the tram station are much better – even if they do seem to appear end-to-end.

From the tram station I went back to the concourse and on to the RER station and RER Line A.

With more than one million passengers a day, RER Line A is the busiest Parisian urban rail line.

With the section of the line running through the city centre closed each summer for maintenance and construction work, much to the dismay of commuters, and with the line badly affected by alerts for suspect packages, which have doubled in the last year, it’s hardly surprising that, according to a 2017 survey by transport authorities in the greater Paris region, trains on RER Line A run on time only 85.3% of the time. Add to that grossly overcrowded trains and the occasional strike and RER Line A can sometimes be a challenge.

Despite the introduction of advanced traffic control systems that enable extremely short spacing between trains during rush hour (under 90 seconds in stations, under 2 minutes in tunnels) together with several upgrades in rolling stock, ever-increasing traffic volume and imminent saturation continues to blight the line.

Still, it’s not the worst performing RER line. According to the 2017 survey, that accolade goes to RER Line D.

The sounds of La Défense – Grande Arche presented in this post are a distillation of my original ninety minute recording now consigned to my Paris Soundscapes Archive but I hope they give you at least a flavour of the sonic tapestry hidden below the monumental Grande Arche de la Défense. In Part 2, I shall explore the sounds up on the surface.

Even with this extensive transport facility complete with its coffee shops and fast food outlets, travelling to and from La Défense during the rush hour each day can be a grim experience. I know, I did it for thirteen years!

Les Cloches de Notre-Dame – The City Singing

WRITING ABOUT PARIS IN his novel, Notre-Dame de Paris, also known as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, published in 1831, Victor Hugo said:

“And if you wish to receive of the ancient city an impression with which the modern one can no longer furnish you, climb – on the morning of some grand festival, beneath the rising sun of Easter or of Pentecost – climb upon some elevated point, whence you command the entire capital; and be present at the wakening of the chimes.”

“… Ordinarily, the noise which escapes from Paris by day is the city speaking; by night, it is the city breathing; in this case, it is the city singing.”

Yesterday, on Easter Sunday, one of Hugo’s grand festivals, I took his advice and climbed upon some elevated point and was present at the wakening of the chimes.

To listen to the city singing, I climbed to an elegant apartment on the fourth floor of a very old building on the Île de la Cité in the heart of medieval Paris and while my elevated point did not command the entire capital as Hugo suggested it should, it did nevertheless command a stunning view of the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris.

From this exclusive vantage point I was able to listen to and to capture the pealing bells of Notre-Dame while being shielded from many of the other sounds that usually surround the cathedral.

Any Sunday morning in Paris will echo to the sound of church bells but the sound of the bells of Notre-Dame are different. Not only do they represent the contemporary soundscape, they also reflect something unique: a genuine soundscape pre-dating the French Revolution.

Les cloches de la cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris:

Bells have rung out from the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris since the end of the twelfth century, long before the building of the cathedral was completed. As the cathedral’s life evolved and its influence developed more bells were added to reflect its increasing importance.

By the middle of the eighteenth century Notre-Dame had a magnificent array of bells: eight in the north tower, two bourdons, or great bells, in the south tower, seven in the spire and three clock bells in the north transept.

But their days were numbered. The ravages of the French Revolution took their toll and the bells were removed, broken up and melted down. One bell though escaped this destruction. The biggest of the cathedrals’ bells, the great Emanuel bell, was saved and reinstalled on the express orders of Napoleon I and it still hangs in the south tower today.

After the dust of the Revolution settled new bells were installed in Notre-Dame: four in the north tower, three in the spire and three in the roof of the transept. Unfortunately, the best that can be said about these new bells is that they were second rate. Poor quality metal was used to cast them and they were out of tune with each other and with the magnificent Emanuel bell. And these second rate bells are what Parisians lived with from just after the Revolution until 2013, when everything changed.

To mark the 850th anniversary of the founding of the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris it was decided to replace the existing cathedral bells with new ones, exact replicas of the bells that were in place before the Revolution. With eight new bells in the north tower cast at a foundry in Normandy and a new bourdon cast in the Netherlands sitting beside the frail and now very carefully used Emanuel in the south tower, once again the soundscape of eighteenth century Paris, lost for over two centuries, could be heard.

Every time I hear the bells of the cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris I pause and remember that I am listening to a very rare thing: a genuine eighteenth century soundscape or, as Victor Hugo would have it, “ … this symphony which produces the noise of a tempest.”

Parisian Politics and a Changing Soundscape

AFTER A VISIT TO PARIS in the early 1950s to record everyday sounds of the city, the pioneering sound recordist Ludwig Koch said, “There is an atmosphere in sound that belongs only to Paris”. For the last ten years or so I’ve been working to record and archive the Parisian atmosphere in sound that Ludwig Koch found so entrancing.

The Parisian urban soundscape is a complex mixture of intricately woven sounds ranging from the spectacular, to the ordinary, everyday sounds around us – the sounds we all hear but seldom stop to listen to, and although I find the Parisian soundscape endlessly fascinating there are two aspects of it that particularly interest me. The first is how the soundscape changes as one moves from the centre of the city to the periphery and the second is how the soundscape changes over time.

Walking from the city centre to the periphery while listening attentively to the surrounding soundscape one can trace not only the city’s physical history but also its social, cultural and political history. For example, the sounds one hears in the centre of the city, in the Champs Elysées, Place Vêndome or Avenue Montaigne lets say, are very different to those one will hear in the rue de Belleville in the east of the city. The sounds of conspicuous consumption emanating from high-end luxury goods emporia and exclusive haute-couture fashion houses in the former stand in stark contrast to a sub-Saharan street market, a Moroccan café or a Chinese supermarket in the latter.

Observing how the city’s soundscape changes over time is important because it gives an insight into the contemporary changes in the social, cultural and political landscape. For example, over the last ten years I’ve recorded many Parisian street demonstrations covering a wide range of issues representing a range of social concerns and political sentiments. Those concerns and sentiments often change over time so by listening to the recordings it’s possible to follow changes in the contemporary social, cultural and political history of the city.

There are many examples of how changing sounds reflect a changing social, cultural and political landscape so I will use one current example to illustrate the point. This I think is a really good example because it’s a hot topic in Paris at the moment.

The story begins 1966 with the then French President, Georges Pompidou.

Georges Pompidou was the French Prime Minister from 1962 to 1968 and then President of France from 1969 until his death in 1974. He was a lover of the automobile and he argued that a freeway should replace the grass-covered banks of the Seine by saying: “les Français aiment leurs bagnoles” (the French love their motors).

On March 27, 1966, the decision was made that the existing roadways along the Seine should be connected to create a continuous expressway along the banks of the river through the centre of Paris. The Voie Georges Pompidou (George Pompidou Expressway) was completed in 1967, and runs along the right bank of the Seine for 13 kilometres from the Porte du Point-du-Jour in the south-west to the Porte de Bercy in the south-east.

Fortunately, there was only room on the riverbank for a two-lane expressway; Pompidou actually wanted to cover the Seine with concrete to create room for an even wider expressway but the environmental movement and others managed to put a brake on that and any further freeway expansion in Paris.

In 2014, as part of my Paris Bridges Project, I went to the Pont Marie, one of the thirty-seven bridges crossing la Seine within the Paris city limits, to record the sounds on, under and around the bridge for my Paris Soundscapes Archive. I discovered that Georges Pompidou’s Expressway ran underneath the arch of the Pont Marie on the right bank of la Seine.

One didn’t have to be an expert in urban soundscapes to realise that the incessant stream of traffic passing under the bridge would impact the soundscape both under and around the bridge.

The Georges Pompidou Expressway from on top of the Pont Marie on the right bank of la Seine in 2014

Let’s scroll forward now to September 2016 when the Mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, signed a decree on behalf of the Paris City Council banning motor vehicles from a 3.3 km section of the berges de la rive droite, the right bank of the Seine, stretching from the tunnel at the Jardin des Tuileries near the Louvre to the Henri IV tunnel near the Bastille, transforming it into a park for pedestrians and cyclists. The Paris City Council debate on the matter was quite contentious but Anne Hidalgo won the day declaring the “end of the urban motorway in Paris and the reconquest of the Seine”.

In 2002, Paris began closing a section of the right bank of the Seine to create a temporary summer beach complete with real sand and sun loungers and in 2013, Anne Hidalgo pedestrianised a 2.5 km section of the left bank.

By comparing the soundscape around the Pont Marie both before and after the 2016 decree we can assess the impact that politics has had on this part of the Parisian environment.

This was the scene from under the right bank arch of the bridge in 2014:

And this was the scene from the same place earlier this week:

And now let’s listen to the sounds of the Pont Marie from the berges de la rive droite in 2014.

Pont Marie from the right bank in 2014:

And from the same place in March 2018.

Pont Marie from the right bank in 2018:

I think the sounds from 2014 speak for themselves: incessant passing traffic creating excessive noise pollution quite possibly having a debilitating effect on our hearing as well as our mental and physical health – not to mention the noxious emissions to the atmosphere.

A political decision in 2016 though has created a completely different sonic environment. Now, the sound of traffic can still be heard from the Quai de la Hôtel de Ville above and behind the right bank, from the roadway on the Pont Marie and from the quai on the left bank opposite, but now the sound of the traffic has become part of the sonic environment rather than dominating it. The sounds that feature now are sounds that could not be heard from the same place in 2014: children’s voices, footsteps, the swish of passing bicycles, the sonic footprint of a passing Batobus, not to mention two Gendarmes on horseback. This part of the right bank has become a completely different sonic experience.

So, was the decision led by the Mayor of Paris to pedestrianise this part of the right bank a good thing?

Anne Hidalgo sees it as part of a comprehensive policy to reduce the number of cars in Paris, one spin-off of which should be a reduction in the amount of noxious emissions added to an already over polluted Parisian atmosphere. The use of diesel engines is already restricted in central Paris and a low-emission zone bans trucks on weekdays.

Although not an expert in atmospheric pollution, I do know something about noise pollution, which is broadly described as unwanted sound that either interferes with normal activities such as sleep or conversation, or disrupts or diminishes one’s quality of life. Excessive traffic and construction work are the major contributors to noise pollution in central Paris, although the construction work is often at least temporary.

It can be argued of course that noise is subjective and we are conditioned by our culture as to how much noise we consider acceptable. If you want to explore more about this I recommend R. Murray Schafer’s seminal book The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World.

For some reason, noise pollution seems to get less attention than atmospheric pollution even though we know it affects our psychological and physiological health and our behaviour.

I hope my examples show that, what ever else it’s done, the pedestrianisation of this part of the right bank has much reduced the noise pollution and generally enhanced the sonic environment.

So, the decision to pedestrianise this part of the right bank is a good thing then?

Well, not everyone agrees. Motorist groups vehemently opposed both left and right bank road closures, accusing the city’s socialist administration of a vendetta against drivers.

Pont Marie from the right bank of the Seine

In February this year, the tribunal administratif de Paris annulled the Paris City Council’s September 2016 decree saying that the decree had been adopted “after a public inquiry drawn up on the basis of an impact study” that “contained inaccuracies, omissions and deficiencies as to the effects of the project on automobile traffic, atmospheric pollutant emissions and noise pollution, which is key data for evaluating the general interest of the project”. The Mayor of Paris immediately launched an appeal and shortly after, signed another decree re-designating this stretch of the right bank a car-free zone.

This debate is much wider than it seems. It’s really a debate that, as France 24 put it, “pits pedestrians against motorists, urbanites against suburbanites, and left-wingers against conservatives, all battling under a hail of studies advancing curiously contradictory traffic, noise and pollution data at the service of competing agendas.”

So much for politics!

I would like to leave you with one other sound from the right bank of the Pont Marie, a sound that simply could not be heard before the 2016 decree.

The second arch of the bridge on the right bank includes a pedestrian walkway and walking through this archway now it’s actually possible to hear the sounds of the river, sounds that were completely subsumed by traffic noise in 2014.

Pont Marie under the pedestrian arch:

Whatever the fate of the berges de la rive droite turns out to be, I hope I’ve shown that a changing soundscape can provide a commentary on the social, cultural and political events of the day.

The Tours Aillaud – Change in Prospect

AT THE WESTERN EXTREMITY of Paris lies the 560-hectare purpose built Paris business district of La Défense, home to an array of CAC40 company headquarters most of which are housed in ultra-modern glass and steel towers.

Just a ten-minute walk from La Défense, in the suburb of Nanterre, lies another set of towers, the Tours Aillaud. Unlike their neighbours in La Défense, these towers are not a glitzy home to multi-national corporations but rather they are one of the many social housing projects created as a response to an increasing housing shortage in Paris after World War II.

An aerial view of the Tours Aillaud via Google Earth

Conceived during the post-war economic boom, these social housing projects, or Grands Ensembles as they were known, were intended to be the embodiment of modernity and innovation. With each comprising several hundred to several thousand homes they were meant to increase living standards for the modern family away from the bustle of the city.

Built between 1972 and 1981 and named after their chief architect, Emile Aillaud, the Tours Aillaud comprise 18 towers housing 1,607 apartments. The towers are of varying heights with the smallest comprising 13 floors and the tallest 39 floors reaching a height of 344 feet.

Belying the notion that suburban social housing could only offer residents shoe-box style apartments, the Tours Aillaud resist straight lines and regularities with a series of connected cylinders, woven together by a labyrinth of passages, alleys, terraces and an undulating paved landscape.

The cladding of each building is made of frescos in ‘pate de verre’ (paste glass) representing clouds in the sky. The French word for ‘clouds’ is ‘nuages’ so the Tours Aillaud are often referred to as the Tours Nuages.

The Tours Aillaud is somewhat of a family affair. Not only was Emile Aillaud the chief architect of the development but his daughter, Laurence Rieti, designed the large snake sculpture that forms part of the playground area near the highest towers and his son-in-law, Fabio Rieti, designed the pate de verre frescos on each building.

As well a designing the towers, Emile Aillaud also incorporated into the surrounding area one tree for each apartment, so over 1,600 trees.

Sounds around the Tours Aillaud:

Sadly, for the most part the post war Grands Ensembles didn’t live up to their utopian ideals as poverty and crime crept in and by the mid 1970s no more were being commissioned. Now, many have been demolished and more are due to be torn down as they age.

While the Tours Aillaud have survived, a confluence of events means that the prospect of change is looming.

It currently costs between €500,000 and €800,000 per year to maintain the buildings. Water seepage through the concrete walls and through the uniquely shaped windows is a persistent cost as is the maintenance of the pate de verre frescos. As the buildings age the maintenance costs increase.

The soaring maintenance costs are one threat to the Tours Aillaud, but another threat comes from the ultra-modern glass and steel corporate headquarters in neighbouring La Défense. The successful La Défense business district needs to expand and to do that it needs to engulf more of the neighbouring suburbs – Courbevoie, Puteaux and Nanterre. The Tours Aillaud in Nanterre are a prime target for this expansion.

Faced with the escalating maintenance costs on the one hand and the La Défense opportunity as they would no doubt see it on the other, the Nanterre local authority and the Département of Hauts-de-Seine have hatched a restructuring plan for the Tours Aillaud.

Although the plan hasn’t yet been finalised, several teams of architects and urban planners are working on the options for the site and they are in consultation with the residents. It seems clear though that the finished plan will include the demolition of some of the existing towers and the relocation of between one third and half the 4,500 people who live there. Some of the remaining towers would be converted to offices, co-working spaces and a hotel while the towers left as social housing would be refurbished and the outside walls reclad with more cost effective materials.

The consultation period runs until October this year and the work is due to begin some time in 2020.

What will become of the Tours Aillaud remains to be seen. Consultation periods in France have a habit of overrunning their original deadline by some distance and projects regularly get mired in beaureaucratic red tape. But no doubt change will come at some point. In addition to seeing how the visual landscape of the Tours Aillaud changes I shall be particularly interested in monitoring how the soundscape changes.

Métro Station Liège and its Sounds

YOU CAN SEE THEM clearly from the train but since the automatic platform doors have been installed it’s now more difficult to view them from the platform, which is a shame because the decorative ceramic panels on the walls add a touch of class to Liège métro station.

Created by two Liège artists, Marie-Claire Van Vuchelen and Daniel Hicter, and installed in 1982, the ceramic panels depict some of the landscapes and monuments of the Province of Liège giving a very Belgian feel to this Paris métro station.

What is now métro station Liège was opened originally as métro station Berlin on 26th February 1911 as part of the Nord-Sud Company’s Line B from Saint-Lazare to Porte de Saint-Ouen.

Paris métro stations are usually named after people, places or events so the station took its original name from the rue de Berlin, one of the streets radiating out from the nearby Place de Europe in the 8th arrondissement. When the First World War broke out in 1914 and anti-German sentiment was particularly strong, the name of the street and consequently the name of the station was changed from Berlin, the capital of France’s enemy, to Liège, a city in the friendly neighbouring country of Belgium.

The ceramic panels are not the only unusual feature of this station.

As part of today’s Métro Line 13, the métro station Liège is located at the junction of the 8th and 9th arrondissements, about three hundred metres north of the mainline railway station, Gare Saint-Lazare. At this point, Line 13 runs directly under the rather narrow rue d’Amsterdam where it bisects rue de Liège.

This part of Line 13 was built using the ‘cut-and-cover’ method of construction. ‘Cut-and-cover’ is a simple method of construction for shallow tunnels where a trench is excavated and roofed over with an overhead support system strong enough to carry the load of what is to be built above the tunnel. The trench for this section of Line 13 was cut down from rue d’Amsterdam and because the street above was narrow so was trench forming the tunnel below. This meant that there was not enough room in the station to accommodate the usual two lines and two platforms opposite each other as is common in most Paris métro stations. Consequently, Liège is only one of two Paris métro stations to have offset platforms.

This rather poor picture culled from Wikipedia shows the offset platforms before the automatic platform doors were installed and it was still possible to see them.

The platform heading south (towards Châtillon – Montrouge) is located north of the junction of rue de Liège and rue d’Amsterdam above while the northbound platform (towards Asnières and Saint-Denis) is to the south of the junction. In each direction of travel, the trains stop at the first platform encountered.

This offset platform arrangement gives rise to a sonic curiosity. You can see from the picture that while the platforms are offset, both the northbound and the southbound tracks pass each platform. This means that this is the only station on the Paris Métro network where it is possible to hear trains regularly passing the platform without stopping. For example, if one is waiting at the northbound platform, the southbound train will pass without stopping and vice versa.

Stopping and passing trains in métro station Liège:

Another interesting sonic feature inside this station is the effect of the relatively narrow tunnel and its curved wall. The wall seems to both amplify the sounds of the trains while attenuating the ambient sounds between trains.

Note: I took these two pictures of the ceramic panels with my iPhone pressed against the glass of the closed automatic platform doors fully aware that at any moment what might seem like my suspicious behaviour could result in unpleasant consequences!

At the outbreak of World War Two, métro station Liège, like several other Paris métro stations, was closed for economy reasons. After the conflict, most of the stations reopened but some of them, including Liège, didn’t and they became known as the stations fantômes, or ghost stations. Liège station eventually reopened in 1968 but only with a limited service and it wasn’t until as late as December 2006 that the station began to operate a full service.

One of the features of Liège métro station is the platform office to be found on each platform. I have visions of them once being occupied by an authoritarian early twentieth-century stationmaster or maybe an equally authoritarian ticket collector. In fact, they date from the twenty-first century renovation of the station.

Of all the features of this station though it is the decorative ceramic panels made up of 6,576 ceramic tiles that dominate. There are eighteen panels altogether, nine on each platform.

On one platform are those designed by Daniel Hicter, each of which has a blue tone:

– Coo, dans la vallée de l’Amblève

– Les premières neiges en Fagnes

– Le barrage de La Gileppe

– L’Eglise romane de Momalle

– Le village de Limbourg

– Le château de Jehay-Bodegnée

– Le circuit automobile de Spa-Francorchamps

– Le château de Chokier-sur-Meuse

– Le Palais des Princes-Evêques de Liège

And on the other platform are those by Marie-Claire Van Vuchelen, each with a brown-ochre tone:

– La vallée du Hoyoux à Modave

– La vallée de la Vesdre à Nessonvaux

– Le Château de Wégimont à Soumagne

– Le Perron de Liège

– L’Hôtel de Ville de Verviers

– Le pont, la collégiale et la citadelle de Huy

– La maison Curtius à Liège

– Le Château de Colonster dans la Vallée de l’Ourthe

– L’Hôtel de Ville de Visé

If you’re travelling on Line 13 of the Paris Métro, it’s well worth getting off at Liège to have a look at these ceramic panels – even if you do now have to peer through the glass panels of the automatic platform doors.