Métro Station ‘Assemblée Nationale’ and its Sounds

RETURNING FROM A recording assignment in the 7th arrondissement the other day, I called into the nearest Métro station, Assemblée Nationale, to catch a train home. Faced with a choice of two entrances to the station I couldn’t resist using the elegant Hector Guimard entourage entrance with its classic red METROPOLITAIN sign, distinctive of the former Nord-Sud line, instead of the rather plain entrance across the street.

The station was opened on 5th November 1910 as part of the original section of the Nord-Sud Company’s line between Porte de Versailles and Notre-Dame-de-Lorette. The Nord-Sud Company (Société du Chemin de Fer Électrique Nord-Sud de Paris) was established in 1904 and built two underground lines, now line 12 and part of line 13. The company was taken over by the Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris (CMP) in 1930 and incorporated into the Paris Métro.

The station was originally called Chambre des Députés, the former name of the French National Assembly, a name the station held until 1989 when it became Assemblée Nationale.

Both the original and the current name of the station of course derive from the Palais Bourbon, the seat of the French National Assembly, the lower legislative chamber of the French parliament, which stands close by.

The Palais Bourbon – The Assemblée Nationale

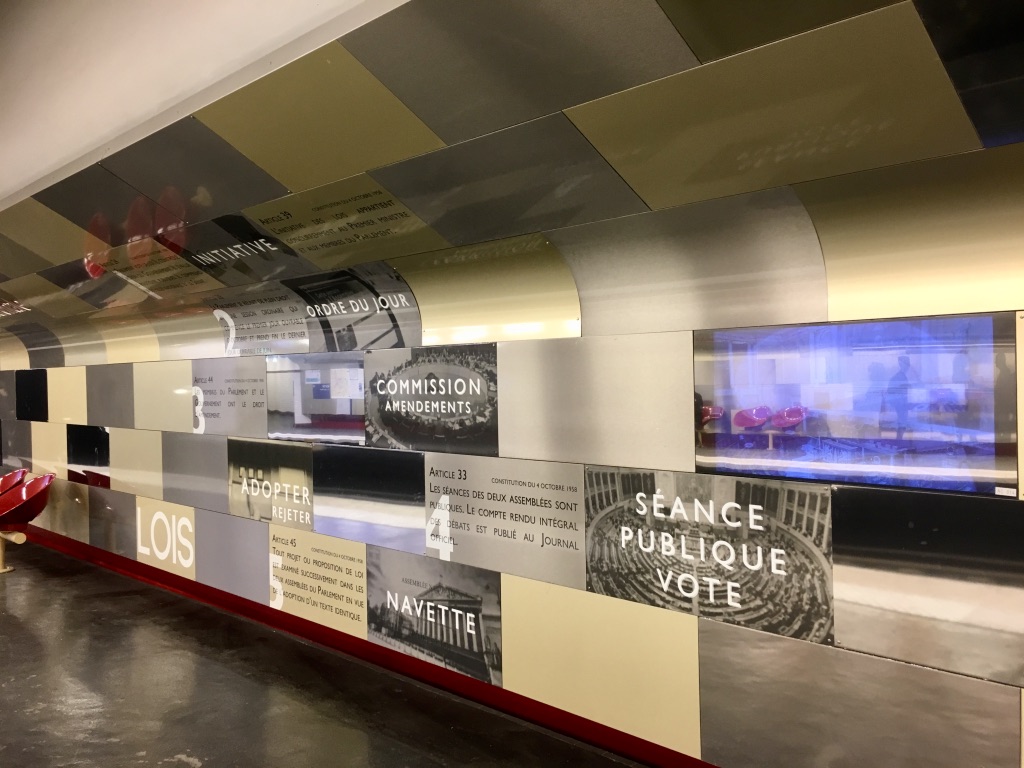

The identifying feature of Métro station Assemblée Nationale is that there are no advertisements anywhere in the station. Instead, the walls sport ninety-metre long murals featuring various aspects of the work of the National Assembly. The murals are changed with each renewal of the legislature.

Both the Palais Bourbon and the Hector Guimard métro station entrance are located in Faubourg Saint-Germain, an aristocratic neighbourhood bristling with government ministries and foreign diplomatic embassies and it was from here that I descended into the station. Once on the platform, I paused to examine the murals and listen to the sounds in the station before boarding a train to take me home.

This is what I saw and heard:

The Métro Station Assembléé Nationale and its Sounds:

The Métro Station ‘Cité’ and its Sounds

WITH ITS UBIQUITOUS Hector Guimard ‘entourage’ entrance, the Métro station Cité is the only Métro station on the Île de la Cité, one of the two islands on the Seine within the historical boundaries of the city of Paris.

The entourage entrance was the most common of Guimard’s Métro entrances. Built in the Art Nouveau style the entrance has waist high cast iron railings around three sides with symmetrical raised orange lamps designed in the form of plant stems, with each lamp enclosed by a leaf resembling a brin de muguet, a sprig of lily of the valley. Between the lamps is the classic Metropolitain sign.

Of the 154 entourage Métro entrances built, some 84 still survive on the Paris streets.

With the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris on one side and the medieval gothic chapel, Sainte-Chapelle, the Conciergerie (a former prison) and the Palais de Justice (all formerly part of the Palais de la Cité, a Royal Palace from the 10th to the 14th century) on the other, Cité Métro station lies at the historical centre of Paris.

The station is on Line 4 of the Paris Métro system, the line that travels 12.1 km across the heart of the city connecting Porte de Clignancourt in the north and, since 2013, Mairie de Montrouge in the south. Until the extension to Mairie de Montrouge was opened, the southern terminus of Line 4 was the original terminus, Porte d’Orléans.

Métro Line 4 was the first line to connect the Right and Left Banks of the Seine via an underwater tunnel built between 1905 and 1907. At the time, this was some of the most spectacular work carried out on the Paris Métro system.

Crossing the Seine was achieved using caissons, assembled on the shore and then sunk gradually into the river bed. The metal structures of the two stations, Cité on the Right Bank and Saint-Michel on the Left Bank, were also assembled on the surface and then sunk into the ground to their final location.

Station La Cité. Fonçage du caisson elliptique à la fin de la station. Vue intérieure. Vers le boulevard du Palais. Paris (IVème arr.). Photographie de Charles Maindron (1861-1940), 18 janvier 1907. Paris, bibliothèque de l’Hôtel de Ville. © BHdV / Roger-Viollet

Image courtesy of Paris en Images

The Seine crossing was commissioned on 9th January 1910 … only to be closed a few days later, a victim of the great Paris flood of 1910.

Cité Métro station was opened on 10th December 1910.

Unusually for the Paris Métro system, the station only has one entrance, at 2 Place Louis Lépine and, unlike other stations on Line 4, the platforms are 110 m in length, longer than the 90-105m platforms at other stations.

Because of the station’s depth, passengers must walk down to a mezzanine level, which contains the ticket machines, and then down another three flights of stairs before reaching platform level. This is fine on the way down but, as I know all too well, it can be a challenge on the way up!

The walls of the station at the entrance at the top and along the platforms at the bottom are lined with conventional white Métro tiles but the decoration of the space in between is curious.

Here, the walls are lined with large metal plates with oversized rivets. I have no idea when these were installed or why, but they give the impression of walking through a huge metal tank.

The station platforms are lined with overhead lamps reflecting the style of the original station lamps.

Until recently, Métro Line 4 had the distinction of using the oldest trains on the Paris Métro network, the MP 59.

Paris Métro train Type MP 59 : Image via Wikipedia

After serving for almost fifty years, these trains were withdrawn from service during 2011 and 2012 and replaced with the MP 89 CC trains from Line 1 when that line was automated.

An MP 89 CC train at Cité station, formerly used on Métro Line 1

Sounds inside Cité Metro Station:

I began recording these sounds at the Cité Métro entrance in Place Louis Lépine, beside the flower market. I went down the steps to the mezzanine level, passed through the ticket barrier, and then descended two more flights of steps. From here, it’s possible to see and hear the trains passing below. I walked along the narrow passageway beside the riveted metal plates and down some more steps to the platform.

Watching and listening to the MP 89 trains entering and leaving the station was quite nostalgic for me since I know these trains so well. When they operated on Line 1, the nearest line to my home, I rode on these trains almost every day for the best part of thirteen years.

I was pleased to see my old friends again at Cité station busy carrying passengers on the second busiest Métro Line in Paris.

Having savoured the atmosphere of the station, all that remained was for me to bid my friends adieu and gird my loins for the climb out of the station back onto the street.

Porte Dauphine – A National Treasure

THE ENTRANCE TO THE Métro at Porte Dauphine is over one hundred years old, it’s a national monument as well as a national treasure and it’s an iconic reminder of the contribution that Hector Guimard made to the Paris Métro.

Construction of the Paris Métro began in 1898 with the stretch between Porte Maillot and Porte de Vincennes linking the west to the east of the city. This, with its subsequent extensions, is what today we know as Line 1. At the same time, two other short lines were built both from Etoile station, which we know today as Charles de Gaulle – Etoile. One of these lines went south to Trocadéro where passengers could alight for the Tour Eiffel and the other went southwest to Porte Dauphine and the then fashionable Bois de Boulogne. These lines were later extended with the former becoming Line 6 and the latter Line 2.

Charles de Gaulle – Etoile to Porte Dauphine:

The French architect, Hector Guimard, was just 30 when he was engaged by Adrien Bénard, Chairman of Compagnie du Chemin de Fer Métropolitain de Paris, to design the entrances to the Paris Métro. Bénard wanted the entrances to be subtle and not to detract from the sophisticated Paris boulevards. Guimard’s devotion to the art nouveau style was a gamble but one which paid off handsomely.

Guimard’s Métro entrances were of two basic types, those with and those without glass roofs. All his entrances were built in cast iron and made heavy reference to nature and the symbolism of plants.

By far the most numerous of his entrances were the ‘entourage’ type, shown above, comprising moulded ironwork roughly waist high around three sides of the stairs with no roof. The specification for this type of entrance called for electric lighting to be included and Guimard solved this by placing two lamps on tall support poles resembling plant stems, in which the orange lamp is enclosed by a leaf resembling a brin de muguet, or sprig of lily of the valley. Guimard also included the characteristic ‘Métropolitain’ sign in his distinctive hand-drawn lettering. Interestingly, the placeholders containing the station name and map were not included in Guimard’s original design; they arrived in the 1920’s. Over 150 of these ‘entourage’ entrances were built of which over 80 survive today.

Guimard’s roofed Métro entrances were known as édicules, and they included a fan-shaped frosted glass awning and an enclosure of opaque panelling decorated in floral motifs.

The Métro entrance at Porte Dauphine is an original Édicule ‘B’ design which Guimard installed at three of the first four terminus stations, Porte Maillot, Porte de Vincennes and Porte Dauphine. The one at Porte Dauphine is the only original édicule to survive. It sits perfectly there displaying its organic forms surrounded by trees and with the enormous Bois de Boulogne close by. The panels have had some restoration and they look as good as they day they were installed.

Hector Guimard of course did not design every Métro station entrance in Paris. His art nouveau style was considered too avant-garde for some areas so, in 1904, the architect Cassien-Bernard was engaged to design a number of new station entrances in a rather austere neo-classical style. These can be found in architecturally sensitive areas including the Opéra, the Madeleine and on the Champs-Elysées.

It has always seemed a little strange to me that Porte Dauphine should be one of the terminus stations on Line 2. Surely the busy hub of Charles de Gaulle – Etoile would have been the obvious choice. However, Porte Dauphine Métro station may not be the busiest station on the Paris Métro network today but in its heyday it was one of the most fashionable and most popular. Had it not been, it would not have been graced with one of Hector Guimard’s finest creations, which today stands proud as a national monument and a national treasure.

Porte Dauphine to Charles de Gaulle – Etoile:

Place des Abbesses

I ARRIVED AT THE METRO station Abbesses by travelling the short, one stop from the neighbouring station, Pigalle, on Line 12.

The Metro from Pigalle to Abbesses:

Thirty-six metres below ground, buried in the former Plaster-of-Paris mines of Montmartre, Abbesses is one of the deepest stations on the Paris Metro network – so deep that a lift is provided to carry passengers to the surface.

For the more adventurous, it’s possible to do it the hard way by climbing the long, winding, seemingly never-ending, staircase. The effort does have its rewards, like the original tiles lining the walls of the stairwell.

Whether ascending by the lift or the stairs, the rewards waiting upon reaching the surface are certainly worth it.

This has to be the most photographed Metro entrance in the world. It’s one of Hector Guimard’s originals and one of only three that are left – the others being at Porte Dauphine and Place Sainte-Opportune. The Abbesses entrance was originally the entrance to the Hôtel de Ville station but it was moved to the Place des Abbesses in 1970.

The Place des Abbesses takes its name from the former Abbey of the Dames des Abbesses founded as far back as 1133 by Adelaide of Savoy, the wife of Louis VI. The reputation of the abbey – and of the Abbesses for that matter – waxed and waned over the years but it managed to survive in one form or another until the French Revolution when it was finally suppressed. Madame de Montmorency-Laval was the last abbess and she came to a sticky end – she was sent to the guillotine in 1794!

If Madame de Montmorency-Laval were with us today, what would she find on the site of her former home?

She would find that there are still ecclesiastical references. The Crypt of the Martyrium, which she would have known well, is the chapel built on the site where, allegedly, Denis, Bishop of Lutetia, (later Saint Denis) was decapitated in 250AD. She would be pleased to know that the chapel is still alive – but only open to the public on Friday afternoons. She would find the Eglise-Saint Jean-de-Montmartre, a more recent ecclesiastical structure, dedicated to Saint John the Evangelist in 1904.

She would be very familiar with the cobblestones in the Place des Abbesses and I like to think that she would approve of the rather delicate sound of traffic slowly rumbling over the pavé which has a curiously romantic feel to it.

She would no doubt find the sound of today’s street musicians in the Place des Abbesses curious but, since music was an integral part of abbey life, maybe she would not entirely disapprove.

I like to think she would also approve of the contemporary creation – the “I Love You” wall – a wall of deep blue glazed tiles with dashes of pink inscribed with the words “I Love You” in over three hundred languages.

All in all, I think Madame de Montmorency-Laval, like the flocks of tourists who visit each year, would be well pleased with today’s Place des Abbesses.

The Paris Metro

Paris has a superb public transport system at the heart of which is the Paris metro.

The man considered to be the “Father of the Métropolitain” was the wonderfully named Fulgence Bienvenûe, a one-armed railway engineer who had great experience of constructing railway systems but no experience of designing urban transport systems. In March 1898, the Minister of Public works authorised the construction of the first six lines of the Métropolitain amounting to some forty miles of track. Fulgence Bienvenûe was appointed Director of Construction for the Métropolitain and he embarked upon his task with enthusiasm.

The construction of the Métropolitain was a huge task. Work began in early 1899 against the background of the other great project of the time, the Universal Exposition, which was to open in the spring of 1900. Unlike the London Underground where deep tunnels were bored, Bienvenûe opted for the cut and cover method of construction. This meant digging deep trenches at the bottom of which the lines were laid and the stations built. Then the trenches were covered over and tunnels formed. This meant that Paris became a huge building site.

Using the cut and cover method of construction the work was able to proceed quickly and the first Line, Line 1 from Porte Maillot in the west to Vincennes in the east, was opened on 19th July, 1900, several weeks after the opening of the Universal Exposition. Line 1was extended much later first to Pont-de Neuilly and then to La Défense. It is the line that I use practically every day.

Bienvenûe continued to work on the metro until his retirement in 1934 at the age of eighty-two. His name lives on today. The metro station Montparnasse – Bienvenûe is named after him.

The work of the other man most closely connected to the Paris metro is iconic, instantly recognisable and is seen as the very image of Paris.

Hector Guimard was commissioned to design all the entrances for the Paris metro in 1902. His name was synonymous with the Art Nouveau movement and his sinuous floral designs in forged iron were produced in sections so that they could be adapted to the conditions of each station. His designs were elaborate with glass roofs and walls and some even included drainage systems. Hector Guimard designed all the entrances to the Paris metro stations until 1913.

Sadly, only two of Guimard’s original metro entrances are still in use. One is at Porte Dauphine, shown here in the photograph above, and the other is at Abbesses although this one was originally at the Hôtel de Ville. Fortunately, some of Guimard’s other metro entrances remain at least in part like this one in the Place des Ternes.

The Métropolitain remains a unique part of the French cultural heritage.

The sound of a metro train on Line 12 at Concorde